Having grown up in Vikasnagar, a small town in Dehradun district, Shrey Rawat began noticing how the educational system in the hills was not helping students connect to their surroundings.

As a child, he witnessed his grandfather lead several social movements in the area and he was inclined to follow suit. In 2023, Shrey and his wife Jyoti Rawat, also an educator, launched Suraah, a ‘living school’ in the valley.

“The idea started taking shape around 2020 when I kept seeing the same story repeat in our villages: children studied to escape the hills rather than feel rooted here. Most ended up in low-paying jobs in cities,” says Shrey, 33, who began his career in education as a Teach For India Fellow in Ahmedabad, and went on to be a part of non-profits such as Central Square Foundation, the NIPUN Bharat Mission, etc.

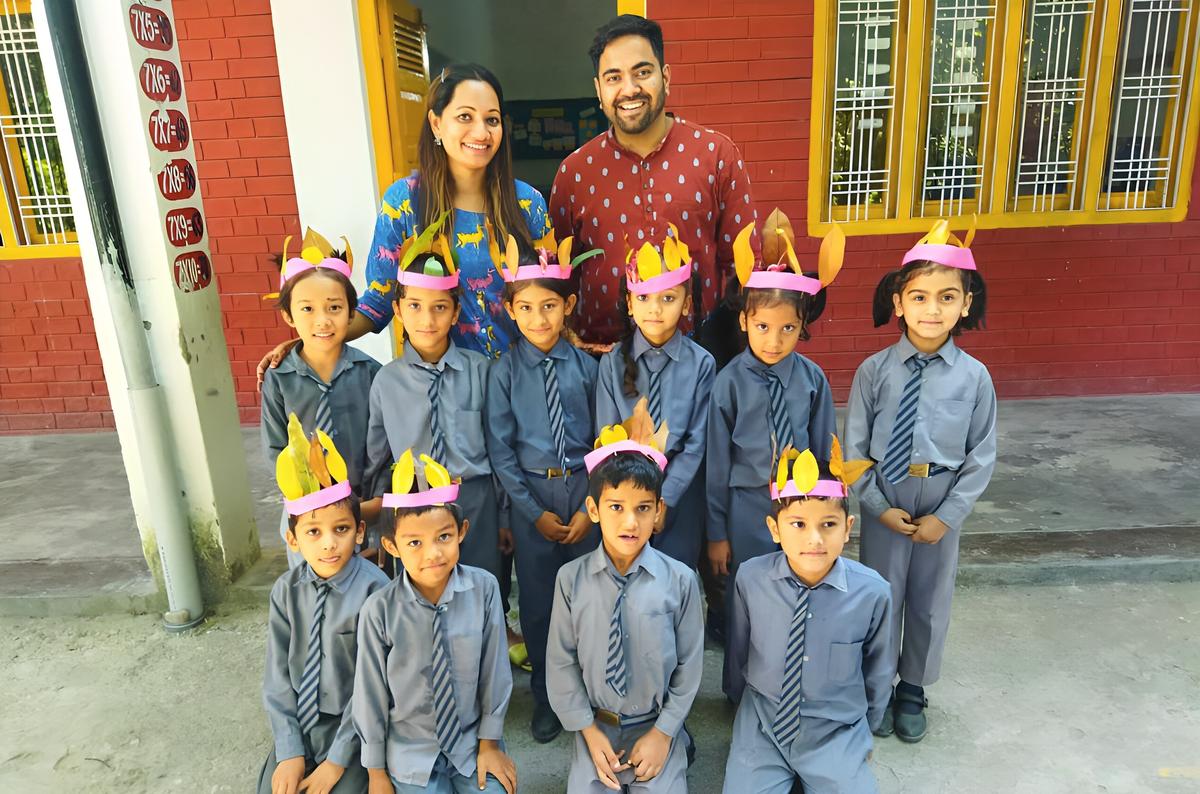

Jyoti Rawat and Shrey with the children at Suraah

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

When the pandemic hit, Shrey spent more time in his village and started speaking to families, teachers, and local leaders. “What I heard again and again was that children needed an education that made sense in the life of the hills. That’s where the seed came from, wanting to build a school model that brings together thinking, feeling, and doing,” he says over a call from the school, adding how they started the pilot in 2023 with one school.

Suraah (meaning an auspicious path in Hindi) is also referred to as the ‘Ulta Pulta’ school and Shrey says this name came about because the classrooms “look the exact opposite of what they expect from a typical school”. Kids learn math outdoors using leaves and stones, understand history by visiting canals, forests, and old community sites, and they paint on walls, not just notebooks. “They ask questions more than they answer them,” says Shrey.

“For the community, this is wonderfully upside-down. So the name stuck.” On a more personal level, he says the name also carries a family legacy. “My grandfather, Surendra Singh Rawat, spent his life in public service and grassroots social movements in the hills in the 70s and 80s. In the region, he is remembered as Suraah-ji.”

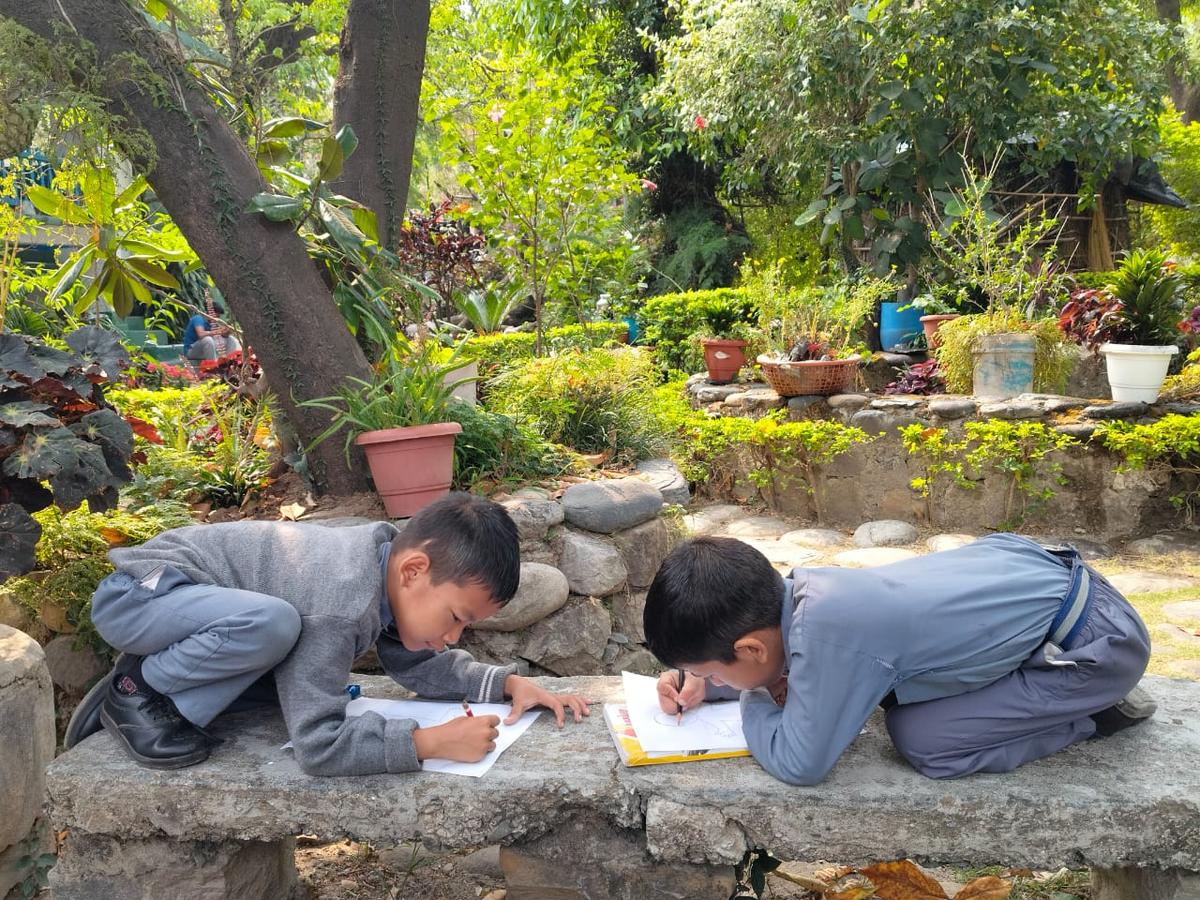

Kids learn math outdoors using leaves and stones, understand history by visiting canals, forests, and old community sites

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

At present, Suraah has around 70 children from Nursery to Grade 5, with eight full-time local teachers, and a few Teach For India fellows who support planning. “Since the school works by adopting and strengthening existing schools, we inherited a school with its own long-standing practices and a committed local teacher team. What we introduced was a clearer structure for how learning and teaching could flow every day. This includes weekly coaching, lesson debriefs, detailed planning routines, and regular observation cycles.”

Suraah (an auspicious path in Hindi) is also referred to as the ‘Ulta Pulta’ school

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Shrey explains that a big part of their growth has come through a partnership with non-profit The Circle India. “Our teachers travel to Pune twice a year for a year-long professional training programme and participate in regular Nature-based learning sessions, rehearsal spaces, and collaborative planning meetings.”

As for the syllabus, every part of the learning connects back to the hills. “Children study rivers, forests, farming cycles, village professions, and migration in Jagatgyan; Nature trails, leaf symmetry walks, and farming observations through Mauj; and in Yogdaan, they identify real village challenges, water scarcity, waste, tourism, and design small impact projects,” says Shrey outlining their modules.

Other branches include Khoj where local materials are used as science tools, Abhivyakti that uses mud, pine needles, stones, and local colours. “The goal is simple: learning should make sense in the world the child lives in.”

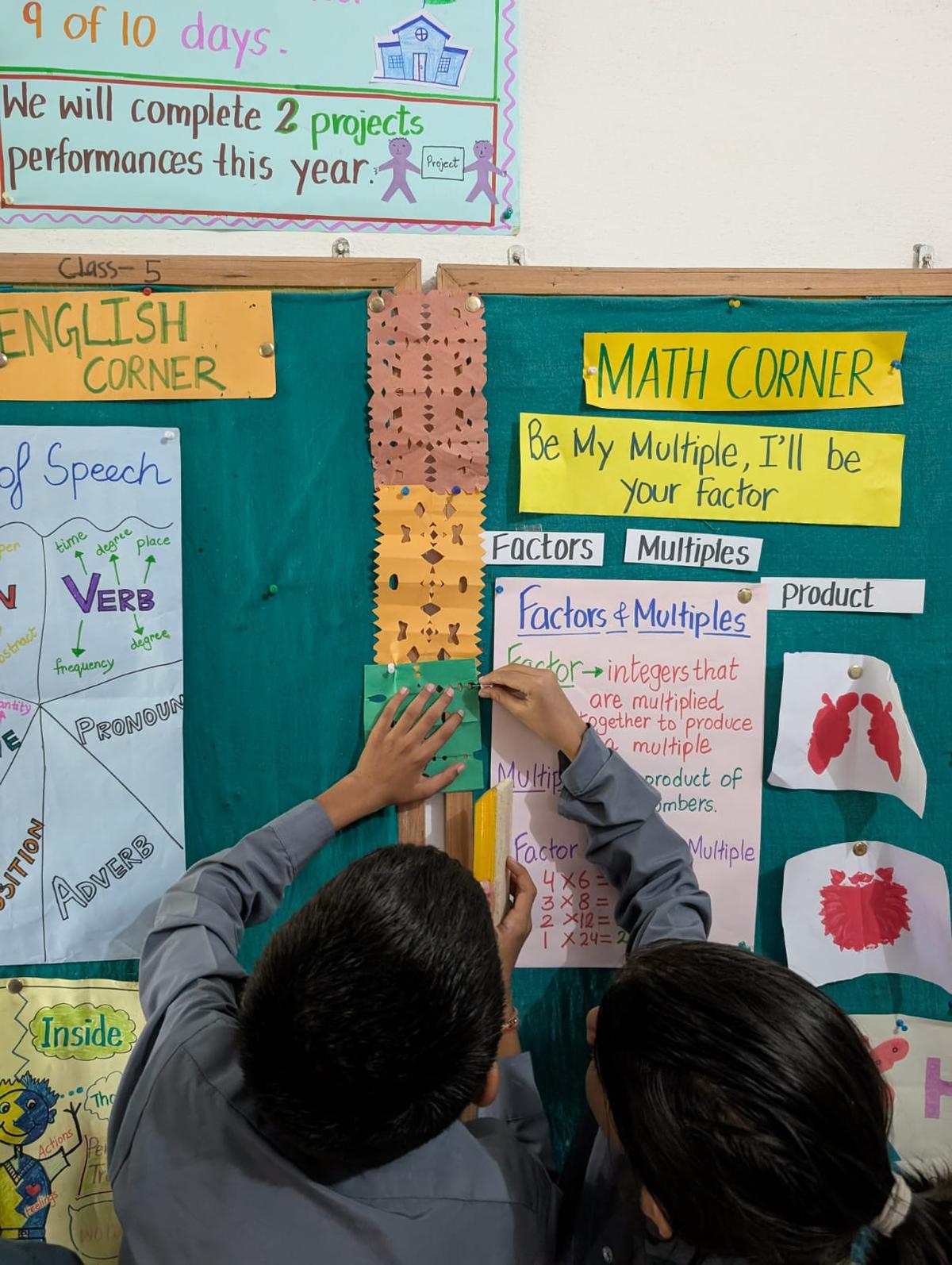

A math session in progress

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

A great teaching methodology, no doubt, but for most people, especially those in the cities, this seems like a utopian scenario given how most mainstream schools function. Shrey believes that a few things are easily replicable across schools.

“First, Nature and community integration. You don’t need forests for that; even neighbourhood walks work. Second, observation-based assessments that include continuous, small, behaviour-focussed notes, not just tests. Schools can incorporate slower classrooms as children learn better with fewer concepts and deeper experiences,” he says, adding that weekly planning clinics for teachers are also important. “You don’t need to overhaul the system to do this.”

The methodology comprises Nature-based learning sessions, rehearsal spaces, and collaborative planning meetings

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Having said that, Shrey admits the challenges of running an alternative school. Some of the biggest, he says, were convincing parents that learning without pressure and punishment actually works, and training local teachers for a pedagogy they never experienced themselves. “One common belief is that progressive schooling is slow, or not serious. The reality is the opposite. It requires stronger planning, deeper teacher training, and a lot more consistency.”

A classroom session in progress at Suraah

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

So far, children who have moved from Suraah to mainstream schools have adapted “surprisingly well.” Shrey adds, “They sometimes find the initial lack of creativity in mainstream settings a bit dull, but academically, they settle in smoothly because their conceptual foundations are strong and they can make sense of new ideas quickly.”

To ensure children can stay on longer, the team is now expanding up to Grade 8, and also setting up a second school site (15 kilometres from the existing school) by April 2026. “Long term, the aim is to build a replicable rural school model for Uttarakhand that is rooted in context and strong in academics,” he concludes.

Details on suraah.org