“We showed the British how to eat Indian food,” says Camellia Panjabi.

Group director of Veeraswamy’s parent company MW Eat, which also runs other fine-dining Indian restaurants in London such as Chutney Mary and Amaya, Camellia is fighting to keep the doors of her 99-year-old restaurant open. Veeraswamy is under imminent threat of closure as its lease remains unrenewed by its landlord, The Crown Estate.

Camellia Panjabi

| Photo Credit:

Urszula Sołtys

Camellia asserts, “The Crown Estate (reporting to the Treasury of the British Government) has terminated the lease of Veeraswamy. And apart from petition and public outcry, we have initiated legal action, arguing that the restaurant has a protected tenancy and that the redevelopment plans are very flimsy. A court hearing is expected between March and June 2026, with the restaurant remaining open until then.”

A spokesperson on behalf of The Crown Estate says, “We need to carry out a comprehensive refurbishment of Victory House to both bring it up to modern standards, and into full use. We understand how disappointing this is for MW Eat and have offered help to find new premises on our portfolio so that the restaurant can stay in the West End as well as financial compensation.” He adds, “The Crown Estate has a statutory responsibility to manage its land and property to create long term value for the UK and return its profit to the UK Government for public spending.”

Camellia counters that it is “common” in England for buildings to be renovated by preserving the ground floor tenants while doing so. “The two entrances of the restaurant and the building are separate,” she says. “Veeraswamy was established and run by British owners for the first 40 years. It is a symbol of great Indo-British cooperation in jointly creating a meeting place for two cultures.” The restaurateur has raised an online petition to Buckingham Palace as well.

When it all began

It was in 1926 that Edward Palmer (the great-grandson of a North Indian Mughal Princess, Faisan Nissa Begum and General William Palmer, Military and Private Secretary to Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of India) established Veerasawmy at London’s Regent Street. He was in England in 1880 to study medicine, but given his passion for Indian food, life had other plans.

Influenced by his maternal grandmother in Hyderabad, he set up a spice business in 1896 and sold pickles, pastes, and chutneys under the brand Nizam Mango Chutney.

With Veerasawmy, Edward aimed at educating Londoners on ‘exotic’ Indian dishes. Sir William Steward, Member of Parliament for Woolwich, acquired Veerasawmy in 1935 and owned it up to 1967. Sir William is said to have travelled over 200,000 miles to and within India and neighbouring countries to find recipes, artefacts and staff. He brought the tandoor to the UK in the early 50’s shortly after it was introduced into Delhi in the late 40’s.

It was then run by a series of Indian owners till Namita Panjabi and Ranjit Mathrani acquired the restaurant and named it ‘Veeraswamy’ in 1996.

The legal battle aside, Camellia is unhappy with the lack of support from Indian counterparts. “Apart from the media writing about the imminent closure of the restaurant, there has been little support from India… Over 20,000 people have signed the petition to the landlord and to King Charles to save Veeraswamy but a majority of the signees are British.”

Memories at Veeraswamy

To Camilla, Veeraswamy “is not just a brand name, a menu, and staff that if you move it you can recreate it”. “There are scores of people who come to dine because their parents and grandparents walked the same steps and sat in the same place in the restaurant, and they came as children. And their parents got engaged or had their first date.”

Veeraswamy in the 1920s

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

UK-based Subha Balakrishnan, founder of beverage brand Bodha Drinks, moved to the UK in 2003 as a student. She recalls visiting Veeraswamy for the first time to celebrate her graduation. “It is not an everyday restaurant; it is an aspirational one where you go to celebrate something special. I went there for my 40th birthday, anniversaries, and it holds so many memories. This is not just for me but for so many others and it is sad to see it fight for its existence.”

Subha adds that its location on Regent Street, one of London’s oldest neighbourhoods is significant: “To have a fine dining Indian restaurant in the heart of London is a matter of pride.”

Subha Balakrishnan (right) with Camellia Panjabi at Veeraswamy

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Iqbal Wahhab OBE, founder of The Cinnamon Club and Roast, has been dining at Veeraswamy for decades. “Nearly 30 or 40 years ago, there were elderly English men who would dine solo to remind themselves of their time serving in India. You could often hear them address waiters as ‘bearer’! The restaurant has been through various owners, not all of whom gave it the care and love it deserved but when Namita Panjabi and Ranit Mathrani took it over, they gave it a new glow,” says Iqbal, who was also editor of trade journal Tandoori Magazine.

He adds that restaurant attracted the great and the good: Winston Churchill, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Charlie Chaplain, among others. “Veeraswamy may not get talked about as much these days as more edgy Indian restaurants like Gymkhana or Dishoom are around but it has an unrivalled place in the history of London dining and the evolution of Indian food in Britain.”

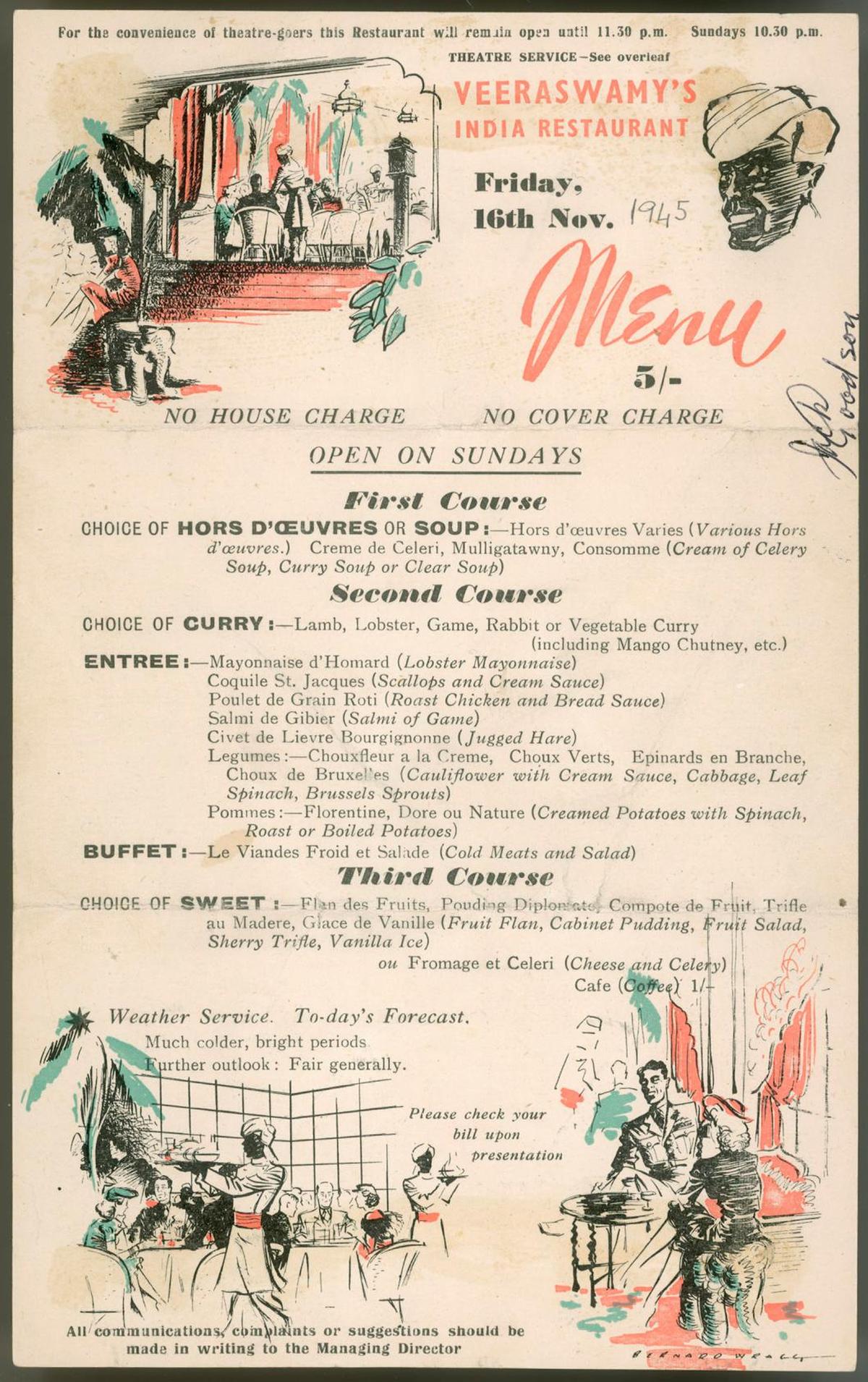

An earlier menu at Veeraswamys

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The present-day Verandah Room at the restaurant

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

UK-based Chef Radhika Howarth explains how Veeraswamy introduced flavours, formats and rituals of dining that were unfamiliar to London when it opened in the 1920s. She adds, “It did more than teach London diners what to eat; it also taught them how to approach Indian food with curiosity, respect and openness. They understood that Indian food abroad doesn’t need to be diluted to be accessible, and never felt the need to apologise for complexity or depth. That’s a lesson many restaurants still struggle with.”

Raj kachori

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

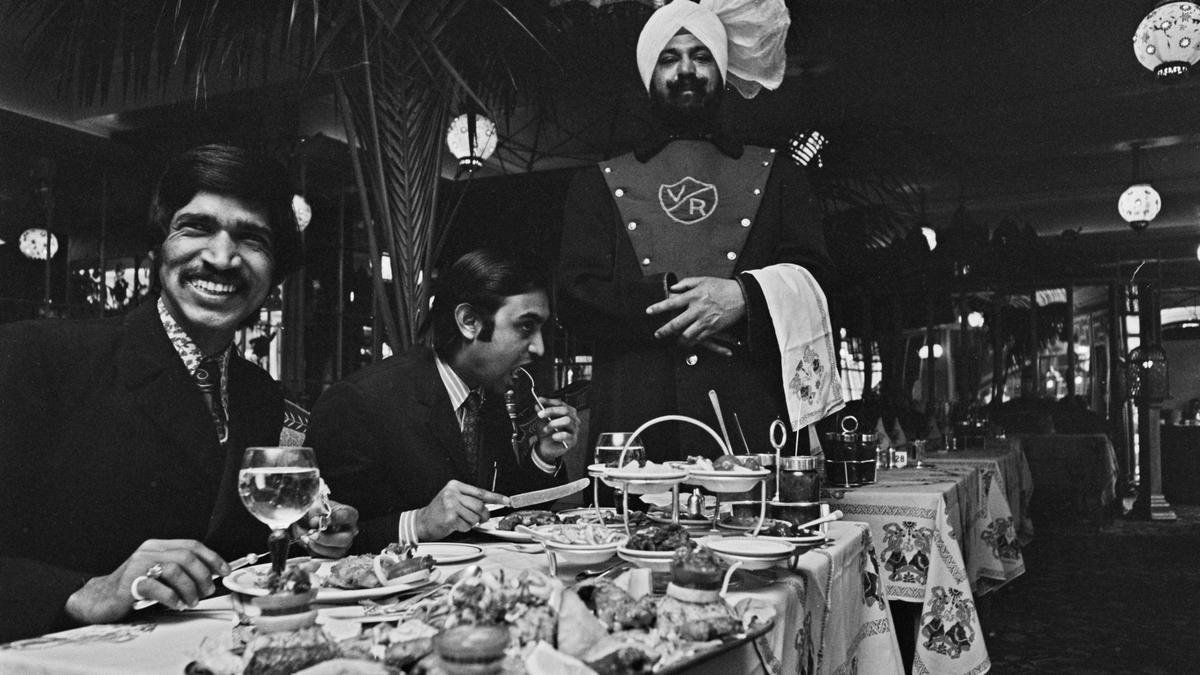

Indian diners at Veeraswamy in the 1903s

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

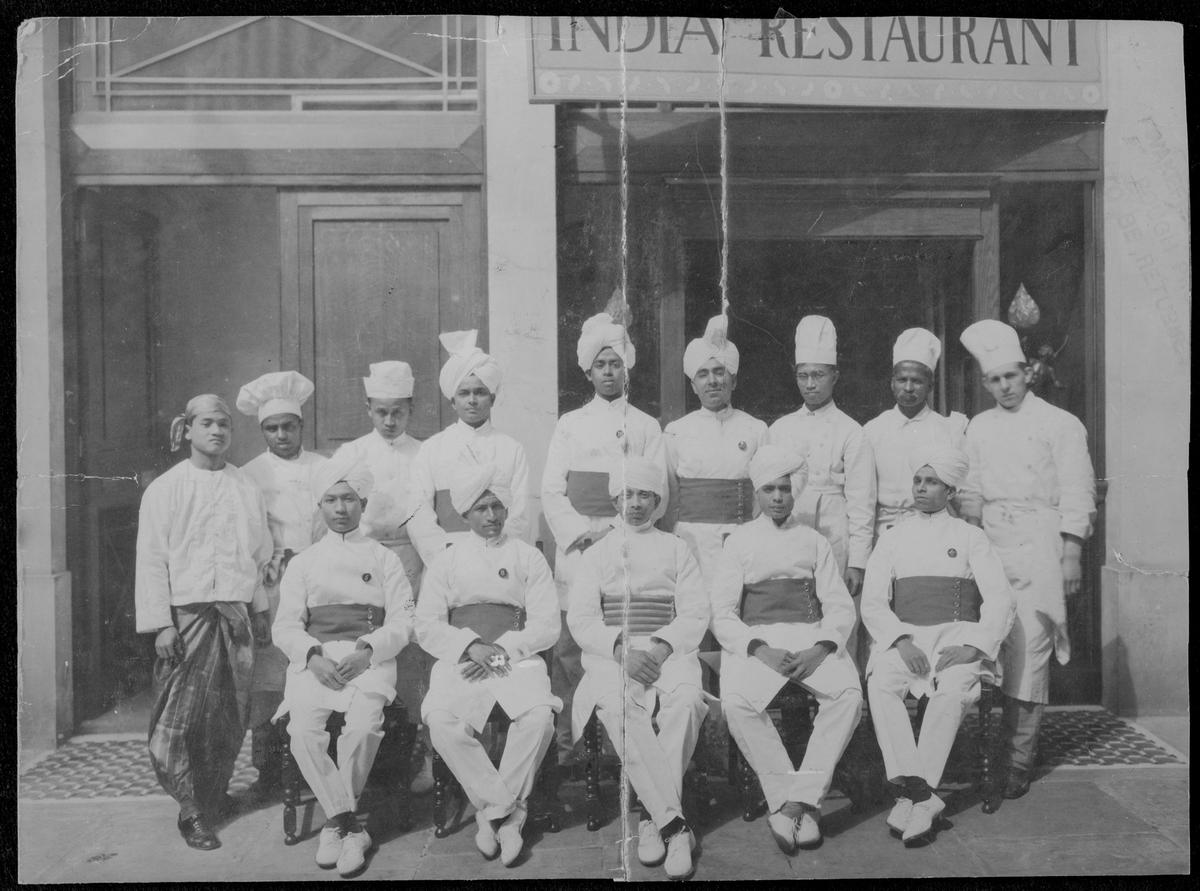

A staff photograph from 1926

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Recalling her last meal at Veeraswamy featuring raj kachori, green masala prawns, and Kerala prawn curry, Radhika says the restaurant is a living archive of Britain’s relationship with Indian food. She adds, “It represents one of the earliest moments when Indian cuisine entered the British dining room not as novelty, but as something to be respected, celebrated and savoured. If a place like this closes, we don’t just lose tables and menus; we lose stories, continuity, and a physical connection to the past. In a city like London, which prides itself on being global and layered, that loss feels particularly profound.”

Published – February 05, 2026 04:19 pm IST