“You can’t wear this shawl to the wedding. Please look for something else as a pullover,” he said. He meant well. He always did.

How could I explain to him that it wasn’t just my favourite shawl? That it had been worn by my mother, my maasi, and both my sisters? That it had been worn by all the women in my family, travelling from Kolkata to Rohtak to Delhi — accompanying every trip and every home.

That my heart had broken the day ash fell on it?

It’s visibly worn. And yet, I still love it. I love it because of the character it has built over the years, the memories it carries.

The writer and her sister with the shawl

In Indian households, closets are rarely just about style. They are memory chests. Every kurta, sari, and sweater is a relic from the people we’ve loved, the people we’ve lost, or the people we’ve outgrown. A hoodie from your first heartbreak; a kurta from college that still smells of freedom. Perhaps this is why inheritance feels instinctive in Indian homes.

And in this moment of time, when AI (artificial intelligence) can help anyone generate images, words, even histories in seconds, when it is increasingly difficult to tell what has been made by a human hand and what has not, such objects take on renewed meaning. A worn sari, an ash-marked shawl carry something no algorithm can reproduce: proof of having lived.

Or, think of it as friction-maxxing — holding close the things that give texture to life (not eliminating the old and the worn in favour of convenience).

In India, we don’t live spare lives, embracing minimalism like the Scandinavians. We accumulate not out of excess either, but because objects here are rarely just functional. They are mnemonic devices. In households shaped by movement, migration, and memory, we learn to live with layers: of fabric, of people, of time.

The earliest memory I have of my mother is her wearing these thin gold hoops. Medium-sized, nothing elaborate, worn every day, with two slender bangles. She has tanned skin and light brown hair that chemo took from her; when it returned, it was black, short, and stubbornly alive. She’s 5’8”, strong-featured, and impossibly kind.

When she handed me those hoops, she gave me everything. Her strength, her beauty, her story. I wear them now. They’re my favourite — by inheritance, not design.

The writer’s mother wearing her thin gold hoops

Stories behind the fabric

Delhi-based author and historian Aanchal Malhotra, 36, speaks to this emotional gravity with her usual poise. “The thing about inheriting objects [even from people you’ve never met] is that the story is a mixture: part memory, part imagination,” says Malhotra, who is also the co-founder of Museum of Material Memory, a crowdsourced digital repository of material culture of the Indian subcontinent.

Author and historian Aanchal Malhotra

She tells me about an orange and grey silk sari once worn by her maternal grandmother. “It’s an unusual colour combination, but striking. I never met her; she died before I was born. But I wondered where she would have bought it from or worn it to. The thing about inheriting objects from people you have never met is that the story is often a mixture of other people’s memories and your imagination. The images are part-borrowed, part-conjured, a mix of nostalgia and curiosity.”

Unusual colour combination of Aanchal Malhotra’s heirloom

For Malhotra, inherited clothes become portals. “I look for remnants — a scent, a tear, a crease in the pleats. Someone ironed it, folded it, chose it once. That act of choosing becomes a part of the garment’s story.” Even when a sari tears, she doesn’t discard it. “I’ve patched, reinforced, reused. Anything to hold on to it. Maybe it’s nostalgia, or maybe some part of a person really is preserved in fabric.”

“There are many objects in my possession. If you are someone who has spent time caring for the past, then objects from the past find you. Naturally, this is a privilege, but it also means that you must carry the stories, the memories, the joy and pain associated with these things and the person they once belonged to.”Aanchal MalhotraAuthor and historian

Gucci bags and bomber jackets

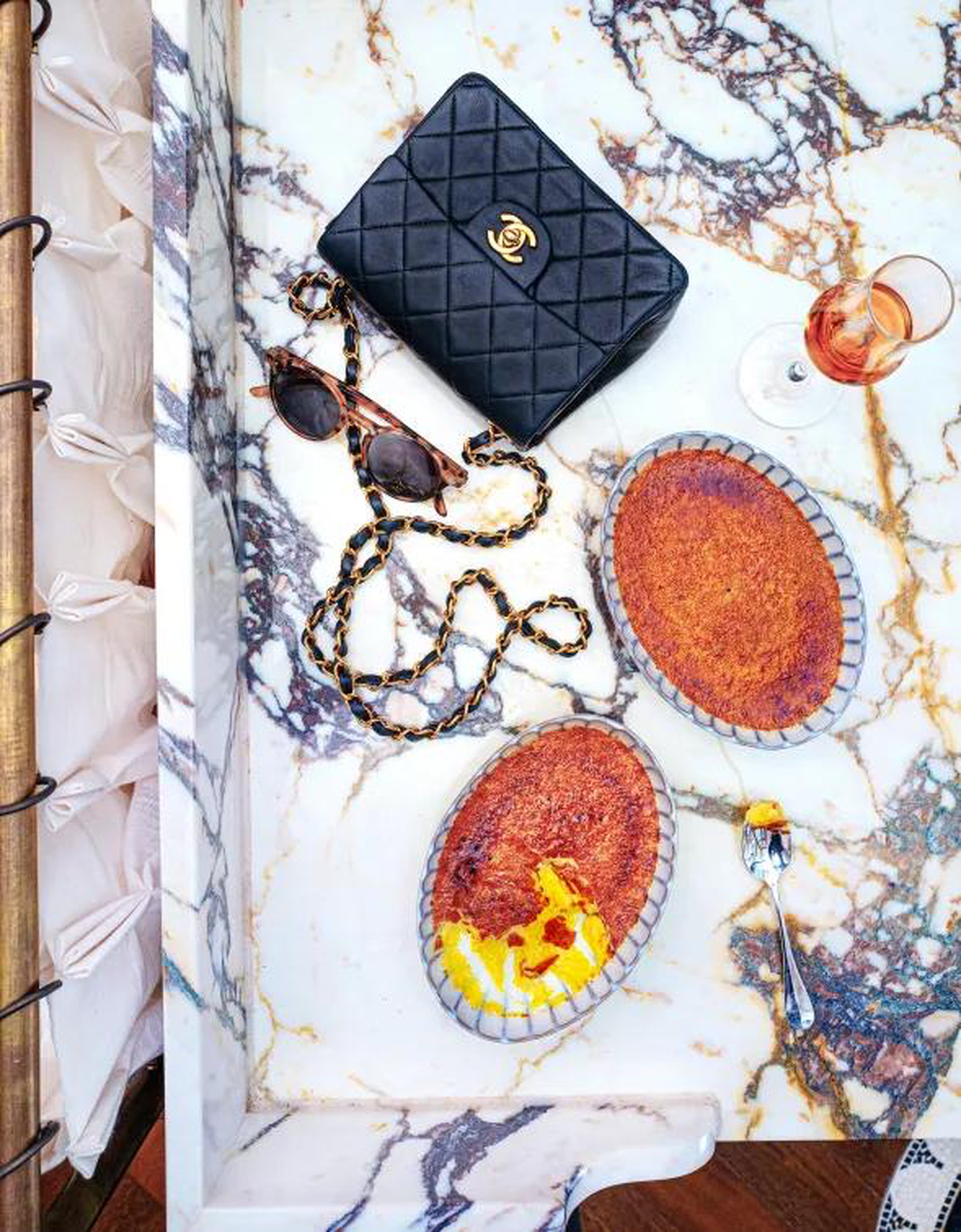

In Mumbai, Samyukta Nair, 40, holds on to glamour with grace. Her favourite pieces come from her paternal grandmother, Leela — vintage Chanel bags, worn-in Gucci, souvenirs from a lifetime of global travel with her grandfather, Captain Nair, founder of The Leela Palaces, Hotels & Resorts. “To this day, I still carry them,” she says. “And I’m often stopped by strangers, unaware that these bags carry decades of stories.”

Samyukta Nair, her vintage bag partly hidden

Samyukta Nair’s vintage Chanel bag

But her most sentimental pieces are the Kanjeevaram and Banarasi saris. “My grandmother wore a sari every day — not for occasion, but as an extension of self. I don’t wear them, but I run my hands over the fabric, catch a trace of her perfume. It’s enough. It brings her back to me. These pieces aren’t just beautiful; they are threads of memory,” says Samyukta, who heads design and operations at The Leela. Inheriting fashion is about passing down values, of craftsmanship, culture, care.

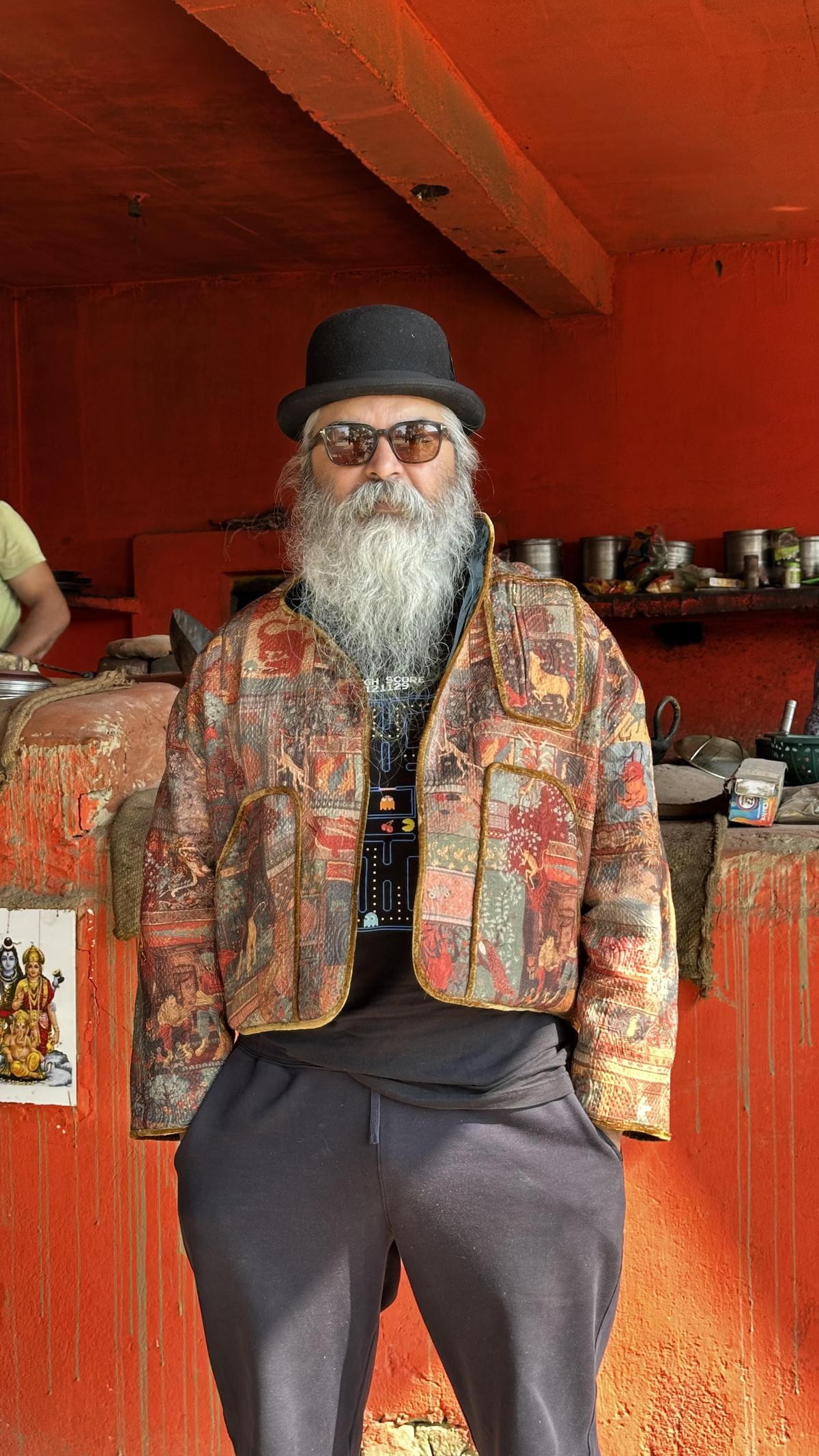

Then there’s Suket Dhir, 45, whose denim jacket from 1973, thick 14-ounce denim, was first worn by his father at 25, passed on to a cousin, and finally reclaimed. “It’s soft now, shaped by time,” he shares. “It softened through wear and took shape, I can never let it go.”

Suket Dhir

Dhir’s own inheritance wasn’t just emotional, it was formative. “I was the coolest kid in boarding school because I wore my grandfather’s high-quality merino trousers. Everyone else had polyester suits. My friends borrowed clothes from me to go home on Sundays.”

“Clothes gather the person who wears them. They carry gestures, posture, mood. That’s their inheritance.” Suket Dhir Designer

He’s already got his daughter eyeing his bombers. “I’m in the business of making heirlooms, not trends,” he says. “Clothes that stand the test of time: silhouette, textile, soul.” But he also lets go of what no longer fits his sensibility. “Not everything needs to be held. Some things need to continue their life on someone else.”

Suket Dhir and his daughter, who is wearing his design

The weight of memory

Dancer and choreographer Anita Ratnam, 71, inherited an archive of Bharatanatyam costumes her mother had designed for her as a young dancer. When they no longer fit, she chose to pass them on. “I gave them away to younger dancers very happily. It felt like giving them my mother’s blessings,” she says.

But the saris her mother bought for her remain. “I won’t give them away. Some are tattered, so I roll them and keep them. I show them to my daughter and tell her, ‘If you don’t want these, I’ll frame them.’” For Ratnam, inheritance is about preserving presence. “It’s like having my mother around. Just keeping her close.”

Anita Ratnam in an heirloom silk sari

| Photo Credit:

Potok’s World Photography

Across the country, in Kolkata, photographer Ronny Sen feels inheritance arrives not as something to be worn, but as something to be held. “My grandfather was an engineer who studied in Belur. The only things I’ve kept close to my heart from the larger family are his khaki INA cap and uniform [from when he was a part of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army],” he says.

The khaki INA cap and uniform

To him, these pieces are relics of a world that feels impossibly distant and unbearably close. The inheritance is martial, heavy. They hold an era’s turbulence, sacrifice, and longing for a nation still in the making. Sen refuses to wear the cap even for a photograph. “I don’t have the courage to. It has the heavy weight of many things.”

Ronny Sen

| Photo Credit:

Twisha

Threads of inheritance

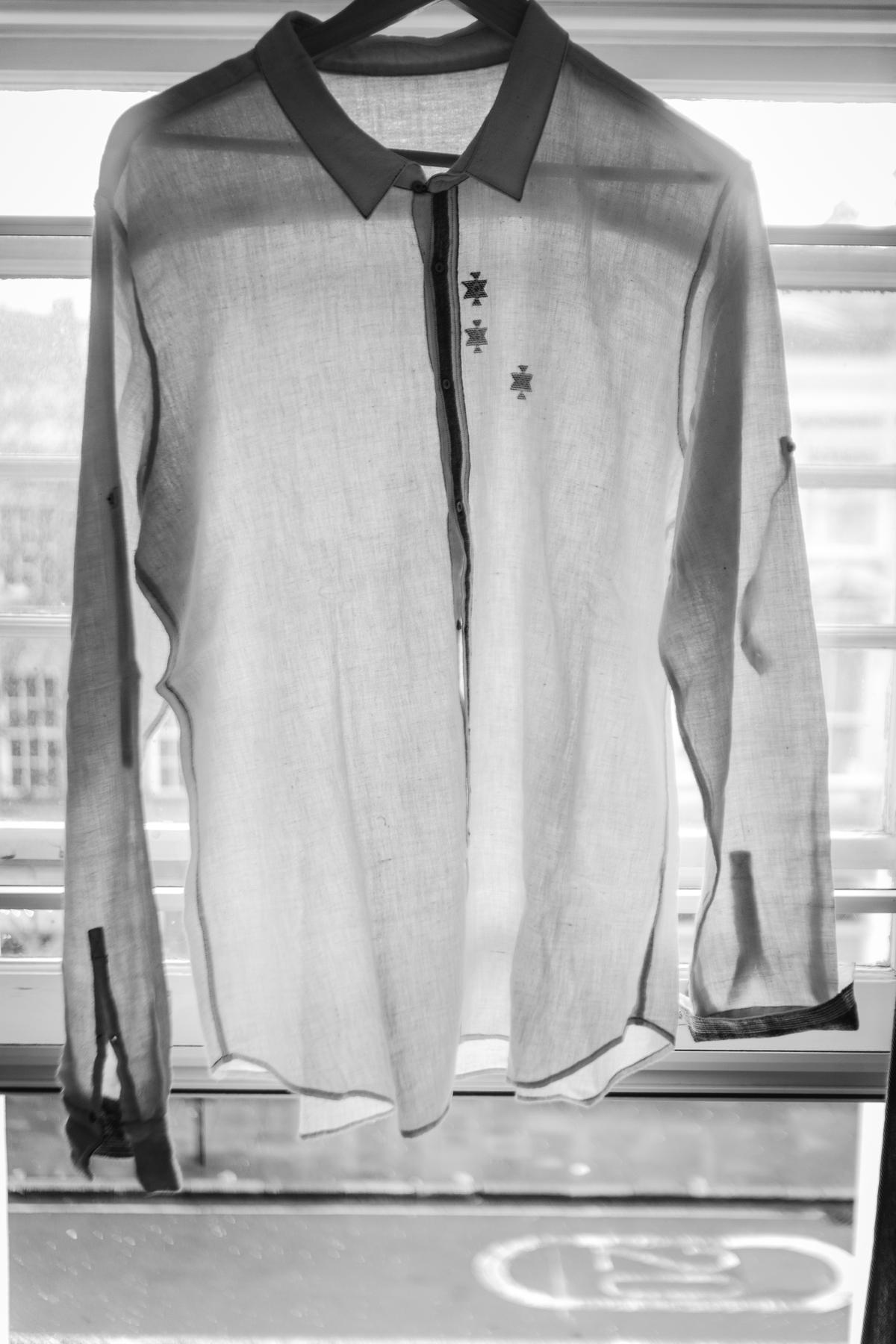

Photographer and documentary filmmaker Gourab Ganguli, 36, speaks of an Injiri shirt gifted to him by Chinar Farooqui, the designer behind the textile-focused brand. “It’s made from fabric sourced from Kutch, which Chinar works with intimately,” he says. “The gift came after I completed a documentary film on the Rabaris of Kutch for her. Once we locked in the edit, she wanted me to have something made by her. I accepted it as a blessing.”

Gourab Ganguli

The shirt is more than just clothing; it carries layers of meaning. “It’s a Rabari fabric, so it connects me to a community and a story I helped preserve. It’s also an Injiri shirt, a designer I deeply value. It’s probably one of the first designer pieces I owned.” He also describes it as an ‘inheritance’. “Chinar and I both come from NID (National Institute of Design), though at different times. The shirt represents our cultural connection, mentorship, and a sense of belonging.”

Gourab Ganguli’s Injiri shirt

| Photo Credit:

Zalak Malde

Another inheritance is a Kashmiri wool khes (a thick blanket, often in damask cotton) that has been in his family for decades. “It got passed around in our Bengali joint family. During winters, cousins took turns to use it. At some point, I simply took it. Not because someone gave it to me, but because I wanted it,” he says. “It’s old now, fragile even… but I want to restore it and maybe frame parts of it.”

Ganguli, who is based between Mumbai and Jaipur, shares that he often gives away things, too. “If something brings someone else joy, I can let it go. And sometimes, I let go because I don’t want to hold a memory anymore. Objects need not always carry warmth.” We become editors of our own inheritance, he believes. “We take what has beauty, craft, culture, and we leave behind what hurt us. That is a form of survival.”

Across each story, one truth emerges: clothes are more than garments. They’re quiet tributes. Carriers of grief. Containers of joy. Sometimes, a shawl is just a shawl. But sometimes, it’s all the people who wore it before you.

“India itself is still healing. We forget our parents and grandparents saw a different world — one without emotional vocabulary. So we inherited their silence, their survival mode. Now, we are the generation trying to build new meaning. Everything we hold is a self-portrait. Even a blanket. Even a shirt. We choose what becomes part of our story.”Gourab Ganguli Photographer and documentary filmmaker

There are clothes we keep because they remind us of someone. Clothes we wear to feel like a version of ourselves we miss. Clothes we let go of — when the grief becomes too heavy, or the memory too distant.

We are no longer together, my ex and I. But the shawl and I, we still are. The memories are heavier now, but I keep them — along with the shawl — because letting go would feel like losing something I’m not ready to part with.

The fashion and culture writer explores people, identity, and contemporary India.