Safeena Husain, 54, was with a group of teenagers celebrating a learning milestone in a small village outside Udaipur, Rajasthan, when she asked one of them why her education had been interrupted. The girl had passed her Class X with Pragati, a second chance programme offered by Husain’s award-winning non-profit Educate Girls. Pragati was designed for older girls who are ineligible for formal schooling. “I’m 18,” she told Husain. “I left education 10 years ago when I was married.”

Husain just won the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award (the first for an Indian organisation) for her nearly two decade old labour of love. She almost didn’t answer the frantic messages she received from an unknown Philippines number on a recent Sunday, asking for “some data and information”, because “I thought it was a fraud”.

Husain empathises with the younger woman’s struggle because today she is one of those rare people who are able to channel their childhood trauma to transform society. Now in celebration mode, she would rather not talk about the difficult days, saying only that it was a “very turbulent” childhood in Delhi. School was always her “place of happiness” and where she felt safe. “Walking home from the bus stop was always the toughest time of day for me,” she says.

Paradigm shift

Husain’s education was interrupted for three years after Class XII. “Everybody gives up on you, they say ‘marry her off’, there’s a divorcee with four kids…” She grappled with that classic triumvirate of guilt, shame, failure until an aunt, a friend from Lucknow University where her interfaith parents met and fell in love, took her home to live with her and changed her life. “She gave me a lot of love, affection and the motivation to go back to education.” Husain eventually graduated with a degree in economics history from the London School of Economics. “I still remember standing on Houghton Street,” she says, referring to the school’s location. “The way I saw myself shifted that day and how the world saw me shifted that day.” Education transformed her life and she wants all girls to know that feeling.

Most girls know education is the only way to get ahead, Husain says. Like the woman who completed her schooling nearly two decades after she left school — and in the same year as her son, scoring more than him. Or the Bhil girls who are the first in their families to get a formal education. And the young woman who left a bad marriage and doesn’t want to unload vegetables at 3 a.m. for the rest of her life.

Husain came back to India in 2005 and started Educate Girls two years later. The non-profit works in about 30,000 villages (mainly in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh). “We have brought over two million girls back into school,” she says. “An equal number have gone through our learning programme, which is the foundational literacy and numeracy programme.”

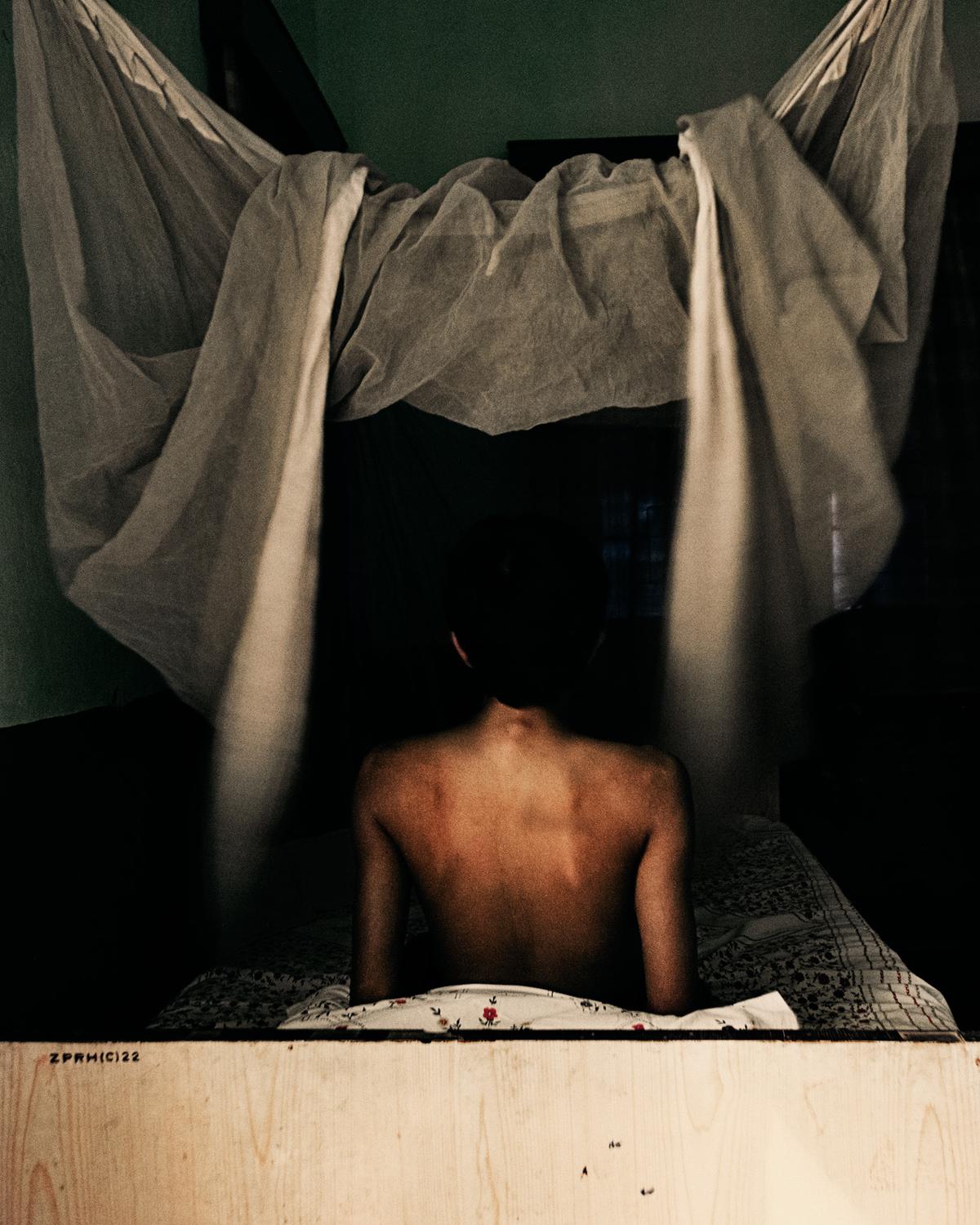

Safeena Husain with schoolchildren

Push for second chances

Some 30,000 girls have graduated from the Pragati programme. “Right now a lot of energy is going into expanding the second chance programme and also taking it to other states,” Husain says. “Because that’s a huge problem, much more rampant than elementary school issues for out-of-school girls.”

Societal and systemic issues can weave an impenetrable wall around girls, forcing them to drop out after the eighth grade. Marriage, household duties and mobility restrictions all become barriers to further education. “For every 100 primary schools, you have 40 middle schools, and 24 secondary schools, which means the distance to school increases and access drops off,” Husain adds.

Those who do stay, face a lot of pressure. “I see a lot of girls approach secondary school with an enormous amount of fear. They have this sword hanging over the head with their parents saying. ‘I’m sending you but if you fail, I’m going to make you sit at home or get you married off’,” she says. “It leads to a lot of anxiety.”

Husain works with state governments and says she’s seen big changes in two decades — from separate toilets for girls to even a campaign such as ‘Beti Bachao’ that acknowledges there is a problem. “You know, the right to education came after we started work,” she says. “So I have seen the struggle, but I have also seen how rapidly progress has happened. I think one must acknowledge that as well because that’s the only thing that gives you hope to continue.” Rajasthan’s comprehensive free secondary education programme for girls has also been a game changer.

Husain’s also seen attitudes come full circle. One father who, many years ago, was against sending his daughter to school recently told her: “You have to educate girls. The world is built for the educated and if we are not educated, we will be exploited like animals.”

Safeena Husain in Udaipur, Rajasthan

Family matters

Like her parents, Husain had an interfaith marriage. She met director Hansal Mehta when she organised a Bollywood dinner for author and Booker Prize winner Daisy Rockwell in Berkeley University. Her father Yusuf, who ran a travel company, was by then an actor in Hindi cinema, and connected her to her favourite director whose 2000 film Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar she had loved.

“We’ve just been together since,” she says. “It was one of those things, you meet and you know it’s meant to be.” The couple lived together for years and have two daughters, eventually only marrying in 2022. “Losing my father during COVID was a big moment,” she says. “It made us feel like we needed to do something more affirmative for ourselves and for our children.”

Her daughters navigate their parents’ very different worlds adroitly. When she was driving through Uttar Pradesh many years ago with one of her daughters, they spotted a line of girls carrying firewood and walking in a single file on the highway. Her daughter immediately piped up: “Why isn’t Educate Girls helping them?”

The writer is a Bengaluru-based journalist and the co-founder of India Love Project on Instagram.