Those small, misshapen apples you hate seeing at the supermarket? Turns out, you can blame bees — or the lack of the tiny, buzzy creatures — for them. New research from the U.S. and Europe has found that the number and variety of bees affect the quality, size, and flavour of apples.

Of course, apple farmers have suspected as much for years. In Himachal Pradesh, Davinder Thakur, 34, an organic apple farmer from Kullu Valley, remembers his grandfather talking about a time when the region only had the local bee species (Apis cerana or Asian honey bee). Their hives were kept in the hollowed-out trunks of old trees and custom-built areas within the walls of houses; the bees were loved and treated like a part of the family. And the apple crop was bountiful every year.

Davinder Thakur’s grandfather taught him the local ways of rearing bees

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Then, a large-scale viral colony collapse in the 1960s prompted the European bee (Apis mellifera or western honey bee) to be introduced to India. This meant the local bees had a tough time re-establishing themselves. Besides competition from the western import, deforestation, an increased use of pesticides, and climate change impacted the bee population. So much so that many farmers now have to rent bee boxes to pollinate their orchards and farms. (The Apis mellifera isn’t always easy to maintain, as it succumbs easily to local predators and parasites, and also needs a lot of flora to feed from — something the region’s seasonal availability cannot provide.)

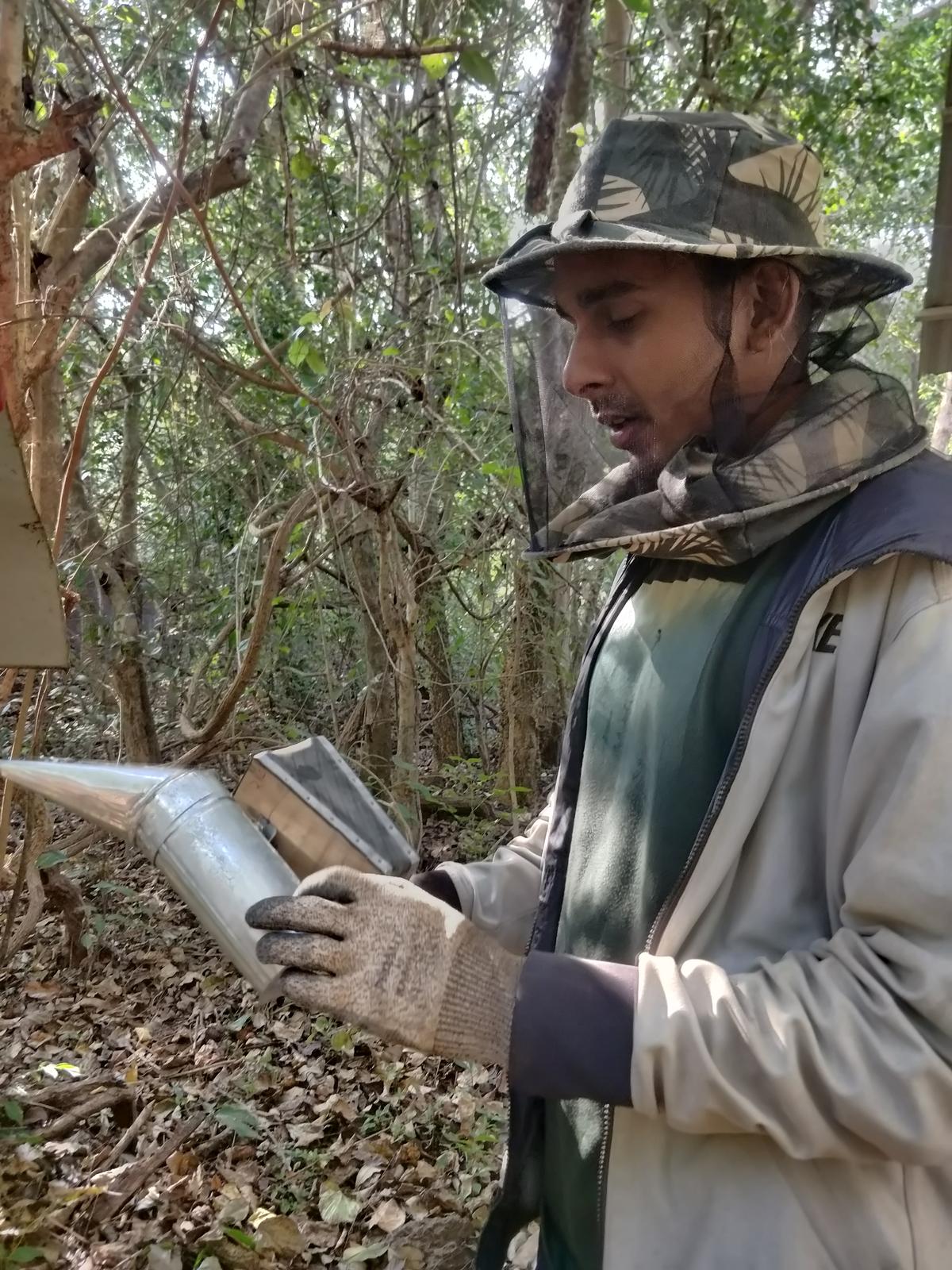

Thakur was eight when his grandfather taught him the local ways of rearing bees. Today, he has more than 100 colonies of the Asian honey bee in boxes. And he is trying to improve his region’s lack. “I have been training Himachali farmers for the past 10 years on how to rear the local bee because of its resilience and resistance to climate change [and parasites], which is a major problem in the mountains,” he says.

Bee boxes at Davinder Thakur’s orchard

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

His organisation, Mountain Honey Bee, offers 25-day workshops that are free of charge (the next is in April). “Having trained almost 200 farmers, it is obvious how badly the area is in need of pollinator species,” he states, adding that farmers have noticed how, within just a few years of improving the local bee population, apple produce always doubles.

The unlikely bee champion

Bees are critical wildlife. Both honey bees and wild bees (think bumble bees, mason bees) are key pollinators. And when over three-quarters of all crop plants in India rely on insects and animals for pollination, it should worry us that bee conservation isn’t making the headlines as much as tigers and rhinos.

Honey bee on the way side in Bhubaneswar.

| Photo Credit:

Biswaranjan Rout

It’s still not too late. As we refine our new year resolutions, we can also take the time to think about biodiversity. Unlike the passive role many of us take in helping 300-kg tigers and 2,000-kg rhinos — signing online petitions, for one — you can save these tiny 0.1 gram ‘buzzers’ from wherever you are. You just need a box and some know-how. Or a few native flowering plants on your balcony.

Speaking to Bengaluru-based Apoorva B.V., 40, the proclaimed ‘Bee Man of India’, you get the feeling one might even be able to build relationships with them. “Bees are special creatures. They have a very developed sense of smell as well as memory, and can recognise human faces,” he says. There is a famous story of the Kondha tribe from Odisha using tamed bees to fight against the British in 1842.

Apoorva B.V. started with two beehives in his bedroom

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Apoorva gave up engineering 18 years ago to turn beekeeper. He started with two beehives in his bedroom, which he kept beside his open window, and now keeps 600 colonies and runs a multi-crore honey business — besides training aspiring urban beekeepers and tribal communities on ethical beekeeping, and saving hundreds of colonies a day, all for free. “I get around 200 phone calls a day from people wanting a beehive removed. I spend up to 8 minutes per call explaining to them how we can live peacefully with bees,” he says, explaining that in countries such as Australia, you can be jailed for killing a bee colony. “Comparatively, up to 500 colonies are exterminated in urban Bengaluru every day. It is high time bees, and all insect pollinators, are put either under the Environmental Protection Act or the Wildlife Act and be protected.”

A local farmer shows a bee hive frame in his honey farm in central Kashmir.

| Photo Credit:

Imran Nissar

His workshops are always full, and the next one is scheduled for February 8, at his farm on Magudi Road in Bettahalli. “The workshops mostly have 30-somethings, and parents who want to introduce their children to nature. Many schools, especially alternative ones, are participating too, like The Valley School and Vidyakshetra,” he says. “Post the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s been a spike with people looking at it as a stressbuster. Beekeeping needs mindfulness; you have to be calm when interacting with bees. They also get a dopamine hit, watching combs being built, and when they harvest honey. I’m seeing people setting up bee boxes on their balconies, and asking apartment complex societies to do it in their common areas.”

“Bees scare people, just like snakes [or street dogs]. Until we educate them, or people like me sensitise them, they will not be able to overcome it. Children are the best to teach this kind of empathy to. They do not come with any prior ‘fear programming’.”Apoorva B.V.Bengaluru’s Bee Man

Apoorva B.V. introducing bees to children at one of his workshops

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Bee trails and more

Another bee champion is Under The Mango Tree (UTMT). Founded in 2009, the organisation helps marginal farmers increase yield through sustainable practices such as beekeeping. At a time when States such as Karnataka have farmers hand-pollinating tomato and chilli plants, hiring local labour to do a job that a few bees can do in just one morning, such initiatives are key.

“Over the last decade, UTMT Society has collected field-level data on how putting bees on farms can increase yields of vegetables such as gourds and tomatoes, most cash crops like cashew and mango, besides oilseeds, by anywhere from 30% to 60%,” says Sujana Krishnamoorthy, executive director of UTMT. “There is anecdotal evidence in [States such as] Madhya Pradesh on increased yields of mahua and chironji seeds from forests due to increased pollinator populations.”

Sujana Krishnamoorthy of UTMT

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Krishnamoorthy has also discovered through her own research (still a work in progress, which will be published soon) that India’s native bees show high floral constancy — consistently foraging from the same flower species — which was earlier seen as a trait only present in the western honey bee. “This finding means that our native bees are better adapted to the needs of our farmers than non-natives [which are being supplied by the government],” she states.

Education can be pivotal. Despite India being home to four native species of honey bees — Apis cerana indica, Apis dorsata, Apis florea and Trigona — public understanding of their importance is limited. Krishnamoorthy is a supporter of beekeeping being taught in schools, especially rural schools where there is space and an inclination to take the training home. “It is an opportunity for children to learn where their food comes from, and get involved in [discussions on] ecology and biodiversity,” she says. “An example I know of an institution doing this is Bhopal’s Barkatullah University, with its bee trail.” Launched last year, on March 3, World Wildlife Day, it features stingless bee (Tetragonula iridipennis) colonies and educational displays. “Initiatives like this can help to create awareness about bees and get the public sensitive to them in their environment, instead of killing them with pesticides,” she says.

Kerala and Karnataka’s stingless campaign

According to data from UTMT, Ahmedabad has the highest number of urban beekeepers, primarily because most homes there have gardens. There has also been a large spike in the number of beekeeping workshops in New Delhi with the advent of Sunder Nursery.

A beekeeper in Cumbum, in Theni district.

| Photo Credit:

Karthikeyan G.

Many State governments, too, are doing their bit to promote apiculture. In Kerala, attempts are being made with stingless bees. These highly social insects thrive in the State’s Western Ghat biodiversity, rubber plantations (a constant source of food) and humid climate. “They are one of the most diverse groups, quiet, with small nests, and often go unnoticed,” says Vinita Gowda from the Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research (IISER), who researches indigenous bee species. “Planting pollen and nectar-rich flowers around you is a good start to support stingless and solitary bees, as is building bee hotels [structures that mimic natural cavities and hollows in wood]. Nesting sites of most bees are under threat, and the exercise of building a bee hotel meets multiple purposes — it spreads awareness in the community while supporting biodiversity.”

‘Planting pollen and nectar-rich flowers is a good start to support stingless and solitary bees’ says ,Vinita Gowda

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

In Karnataka, too, meliponiculture (stingless bee keeping) is picking up. In Dakshina Kannada, the Gramajanya Farmers’ Producer Company (FPC) has launched a ‘honey at every home’ initiative to promote it in urban areas — selling bee boxes with colonies, and also helping maintain them if bee enthusiasts need help. Mangaluru is the main focus, among other urban areas.

“We must see native bees as pets, not pests. Even in dense cities, people living in houses with balconies can keep bee boxes [stingless bees are ideal, after some training]. The bees will collect nectar from trees within a two-to-three-kilometre radius and return to your house. You’ll have a hobby, and they’ll help in pollination”Amit GodseBee Man of Pune

Amit Godse during a beehive relocation

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Government needs to buck up

With climate change becoming more pronounced, “being a farmer today is one of the most difficult livelihoods in our country — and yet, the most necessary”, says Peter Fernandes, a Goa-based beekeeper and pioneer of permaculture. Bees can’t be separated from this discussion. “We must make it clear to our leaders that we care about the environment and, more importantly, our food. Farmer groups and citizen movements, along with private research organisations like ATREE [Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment], need to come together to make their voices heard.”

Peter Fernandes with his bee hives in Goa

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Government attempts, at the moment, are lacking. Yes, the Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) distributes a large number of bee boxes across India, facilitates honey production, and helps rural households benefit economically.

But, as Krishnamoorthy shared with the Magazine some time ago, “Which farmer can spend ₹3 lakh to buy 50 boxes [a few years ago, a bee box cost ₹3,500 and the Mellifera cost another ₹3,000; prices have changed since]? Instead, give a small farmer ₹2,000 of support for boxes [UTMT’s cost ₹1,000] and training to transfer local bees from the wild and rear them, and you give them a low-cost way of adding to their yields through pollination and to produce honey.”

Apoorva tells me a story about the government sending the Apis mellifera to tribal regions in Chhattisgarh, where the people couldn’t take care of the bees because they are migratory. Medha Monteiro, a beekeeper of almost a decade and president of the Bardez Beekeepers Society (BBS) in Goa, says, “There wouldn’t be a need for our society if the KVIC or the National Bee Board did a competent job of teaching and equipping citizens with proper equipment.” Before joining BBS, she says farmers and urban beekeepers alike have reported issues with sub-standard bee boxes (made with poor-quality wood, and gaps between boards), missing queen bees, or insufficient combs.

Medha Monteiro, a beekeeper of almost a decade

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Genetically modified insects?

Though bees contribute to approximately 20% of total crop yield (according to a 2023 paper), we don’t have numbers for bee population loss. Gowda from IISER says, “There is unfortunately no long-term data in India on any insect, let alone bees. This is not a fault of funding, but a lack of interest and understanding of the importance of these creatures within the scientific community. However, we know from studies outside of India that chemicals have affected bees’ navigation, nesting and survival. It is the same as habitat loss.”

A new study by researchers at the University of Sussex and Rothamsted Research in the U.K. found that sites sprayed with NPKS (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potash, Sulphur)-based fertilisers halve bee populations. Strikingly, the research also found 95% greater pollinator abundance and 84% greater pollinator species richness in untreated plots.

So, it’s ironic that last October, the Union Cabinet, headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, approved ₹37,952.29 crore for farmer subsidies on Di Ammonium Phosphate (DAP) and NPKS-based fertilisers. Pushing the irony further is the Government of India’s initiative for beekeeping in 2025-2026 — a total outlay of ₹500 crore. This is a systemic problem and shows the inherent contradiction within the broader agricultural policy of the country.

Keenan D’Costa, has been keeping bees as a hobby at his home in Goa

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Meanwhile, another initiative could also cause equal damage. In the 2025-26 budget, the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) received an overall allocation of ₹3,446 crore (a 50% increase from the previous year) to support biotechnology startups, including genetically modified insects. Yes, you read that right.

India has guidelines for these insects, but the potential for unforeseen ecological consequences from their release is a major concern. “Even the effect of non-native insects is unpredictable and has been known to go rogue [like the cane toads introduced in Australia that killed native predators]. We have no idea how a genetically modified one will affect its environment,” says Gowda. They could lead to irreversible ecological disruptions by altering populations of pollinators, pests, and decomposers, which can have cascading effects on entire food webs.

What you can do

Support eco-friendly farming: Whenever possible, choose food grown with fewer chemicals and less plastic packaging. Organic or agroecological systems tend to be better for pollinators, and the planet.

Plant with purpose: Whether it is a balcony box, school garden, rooftop, or community field, every flowering space counts. Try to grow a mix of native plants that bloom throughout the year, such as hibiscus, tulsi, marigold, to support a variety of pollinators. Those who have lawns, keep some pollinator-friendly spaces without mowing everything.

Go pesticide-free: Avoid using pesticides, herbicides, or fungicides where possible.

Reduce night lighting: Install outdoor lights on timers or motion sensors. Nights are crucial for many pollinators, particularly moths, which are also vital to pollination.

Speak up in your community: Encourage local leaders to support pollinator-friendly practices, such as planting along roadsides, creating urban gardens, and regulating plastic waste.

Support pollinator-friendly habitats: Energy and climate solutions can also benefit pollinators, if designed wisely. Solar farms planted with wildflowers such as goat weed (Ageratum) and tridax daisies (Tridax procumbens), or reforestation that includes flowering species, offer multiple wins.

Protect wild pollinators: Managed honey bees are just one part of the story. Support efforts that conserve native wild bee species.

Share your knowledge: Host a workshop, write a blog, record a video, or simply talk about it to build pollinator protection culture.

A shift in perspective

One of the fundamental problems today is that India’s beekeeping policy is treated as a standalone livelihood sector, divorced from agricultural and environmental policy. Until the country integrates pollinator health into its core agricultural framework — by drastically reducing harmful pesticides, promoting ecological farming, and conserving natural habitats — other efforts will remain a palliative measure.

The most powerful action now is a shift in perspective, from seeing bees as just honey producers to recognising them as essential, vulnerable wildlife that sustain our food systems. By creating pockets of safety, food, and habitat, citizens can build a resilient network of sanctuaries that no single policy can achieve alone.

The writer is a permaculture farmer who believes eating right can save the planet.