India boasts a vast and diverse surface water network. This water is an interconnected network of natural water bodies like rivers, lakes and ponds. The major rivers in India being Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Godavari along with countless lakes, ponds and traditional water tanks. These water bodies support agriculture, drinking water supply, and groundwater recharge while also playing a role in cultural and ecological preservation. From the lakes of Kashmir to the stepwells of Rajasthan, water storage and conservation have been integral to India’s history.

A devotee takes a holy dip in the Ganga river during sunrise, in Varanasi.

Surface water is like India’s lifelines. India’s permanent surface water resources are divided in three categories: Lakes, rivers and wetlands.

Rivers

The major river systems in India that include the Ganga, Brahmaputra, Indus, Godavari and Krishna, provide water for agriculture, drinking and hydropower. These rivers, acting as the backbone of India’s water supply, are nourished by monsoons, glaciers, and tributaries. The Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna system is the largest river network in India, contributing significantly to the surface water availability.

Lakes

India is home to both natural and man-made lakes. Famous natural lakes include Dal Lake (Jammu & Kashmir), Chilika Lake (Odisha), Loktak Lake (Manipur), and Sambhar Lake (Rajasthan). Many artificial lakes, such as Udaipur’s Lake Pichola, were created for water storage and irrigation.

Vegetable sellers wait for customers on the bank of Dal Lake in the backdrop of ranges covered in fresh snowfall, in Srinagar.

Quick facts

Largest Lake (Overall)

Vembanad Lake, Kerala – The largest lake in India, covering around 2,033 sq. km.

Largest Freshwater Lake

Wular Lake, Jammu & Kashmir – One of the biggest freshwater lakes in South Asia.

Deepest Lake

Manasbal Lake, Jammu & Kashmir – With a depth of around 13 metres, it is considered India’s deepest freshwater lake.

Largest Brackish Water Lake

Chilika Lake, Odisha – Asia’s largest brackish water lagoon, famous for migratory birds.

Highest Lake

Tso Lhamo Lake, Sikkim – Located at about 5,330 meters above sea level, making it one of the highest lakes in the world.

Saline Lake

Sambhar Lake, Rajasthan – The largest inland saltwater lake in India, known for salt production.

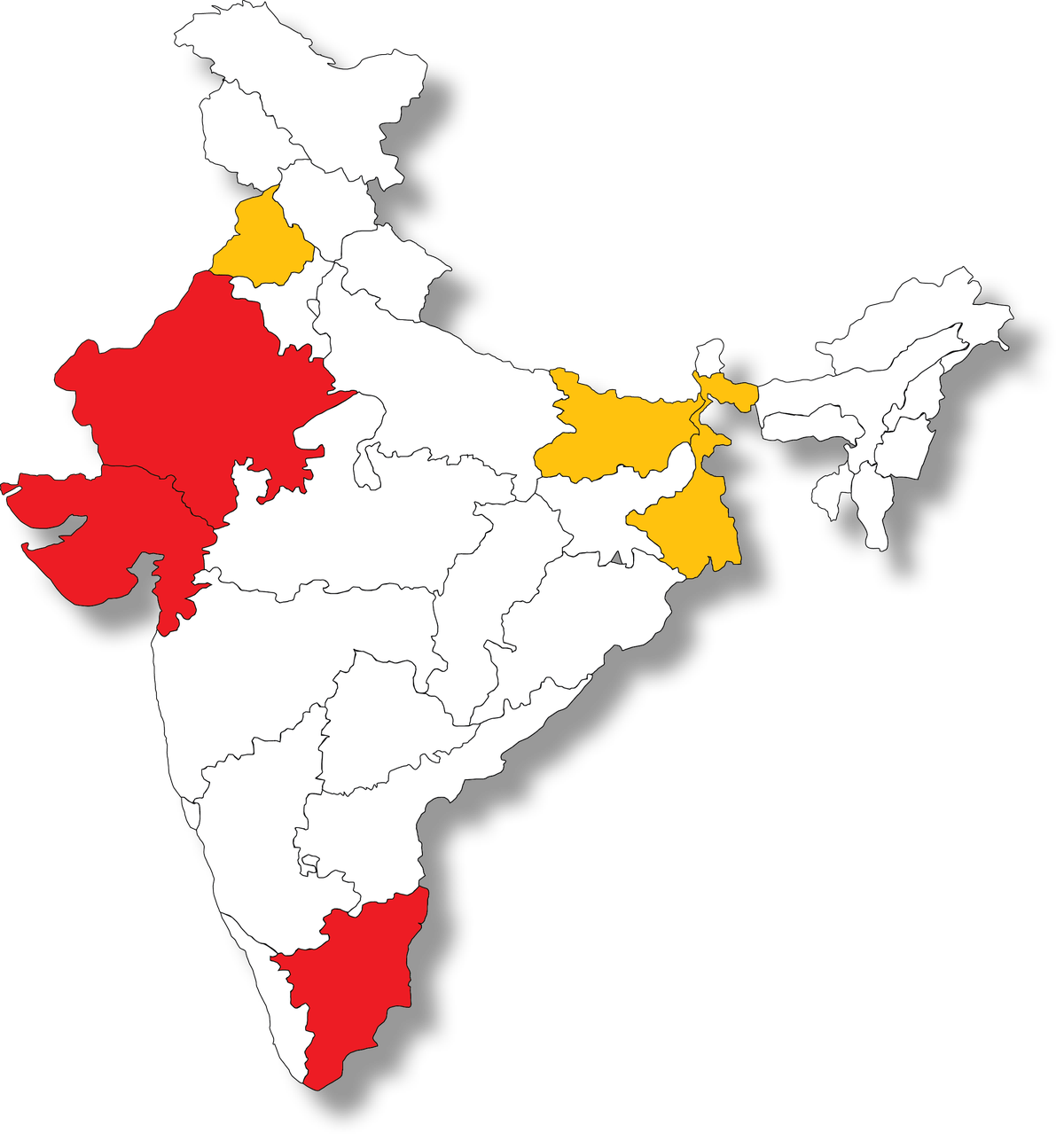

Status and Distribution

India’s surface water resources are spread across various regions, with some states playing a leading role in specific categories. West Bengal has the highest number of ponds and reservoirs, while Andhra Pradesh has the most tanks. Tamil Nadu leads in the number of lakes, and Maharashtra is known for its extensive water conservation schemes. These water bodies are crucial for sustaining ecosystems, supporting agriculture, and meeting domestic and industrial needs.

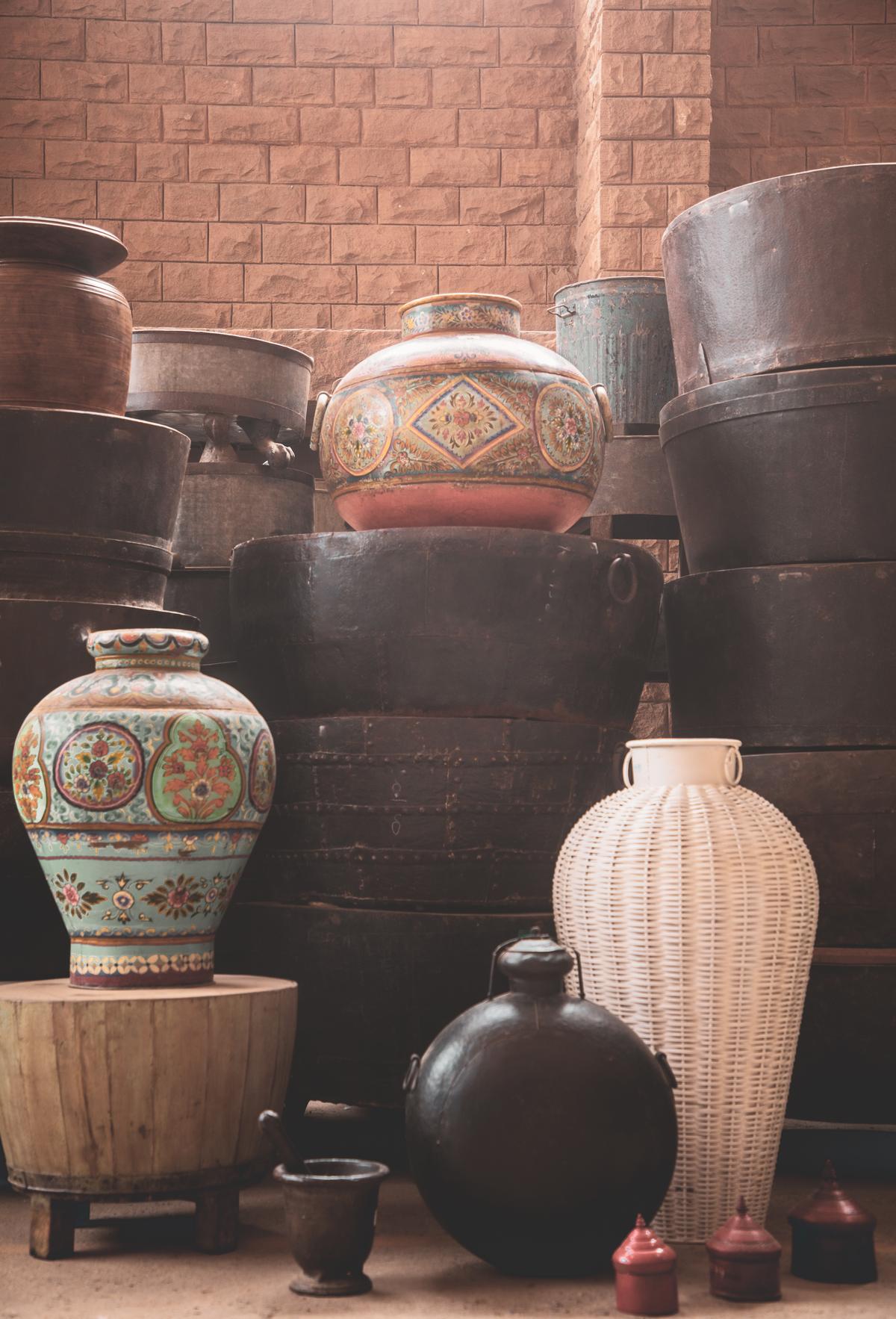

Ponds, tanks & stepwells

Traditional water bodies like stepwells, temple tanks, and village ponds have historically been lifelines for rural communities. These small reservoirs helped store rainwater for irrigation and drinking purposes but are now at risk due to urbanisation and neglect.

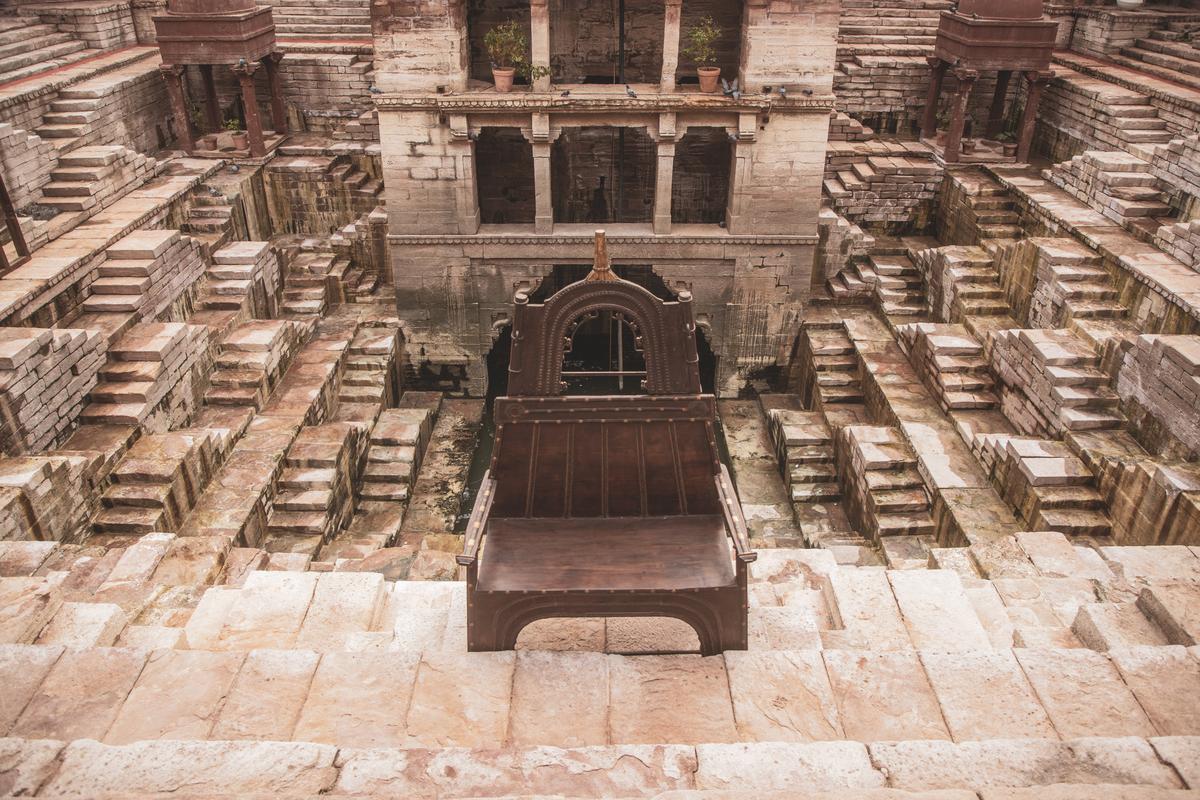

Unique Stepwells and tanks

India’s rich tradition of water conservation is reflected in its stunning stepwells like Rani ki Vav (a UNESCO site) and Chand Baori (one of the deepest). Historic structures like the Kallanai Dam, built over 2,000 years ago by Karikalan Chola, still support irrigation, while temple tanks like Pushkar Lake highlight the country’s sustainable water practices.

Sacred temple tanks: Many temples in South India have large water tanks, such as Madurai’s Meenakshi Temple Tank and Kamal Pushkarini in Hampi, which were once crucial for religious rituals and water conservation.

Rani ki vav

| Photo Credit:

Madhuvanti S Krishnan

Pollution

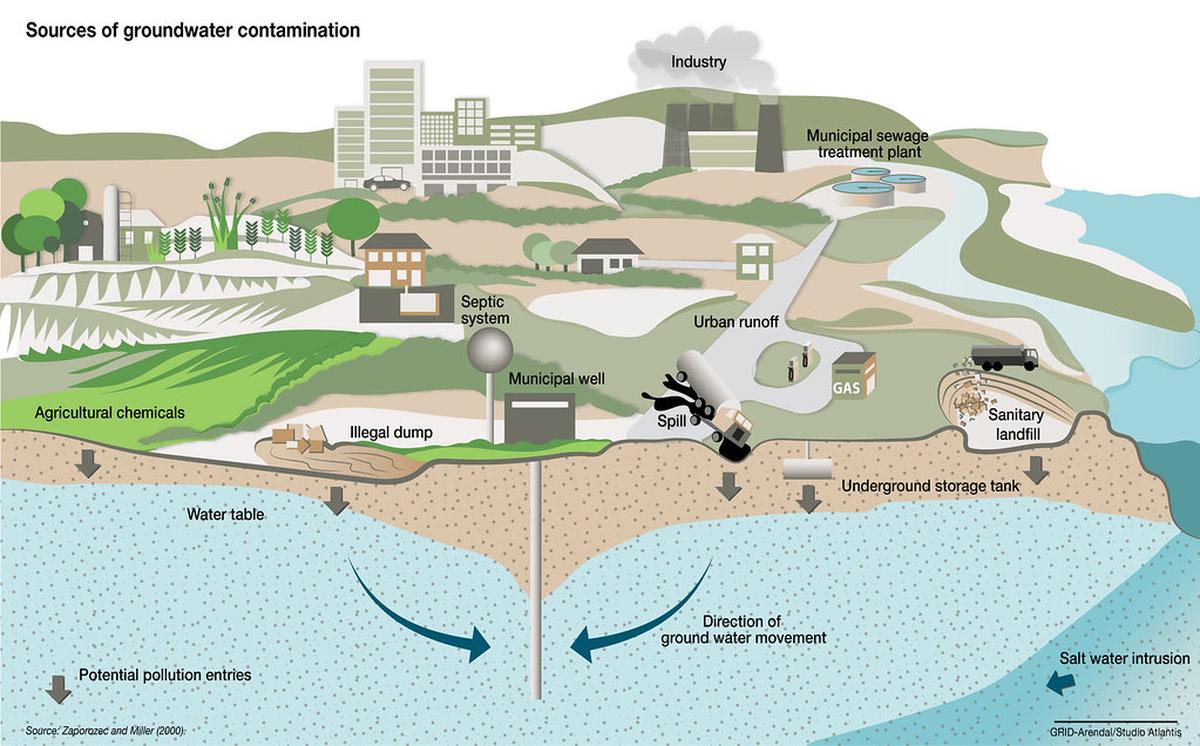

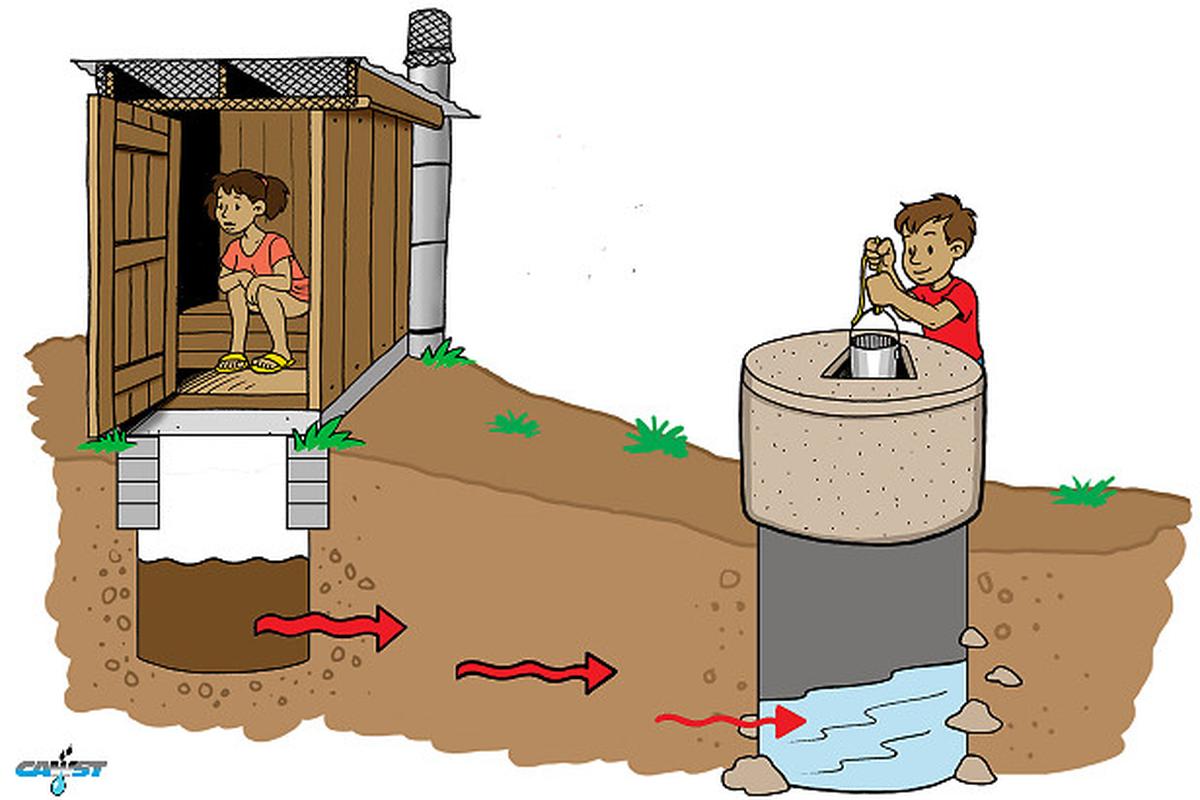

Industrial discharge, plastic waste, and untreated sewage are major pollutants contaminating rivers, lakes, and ponds. The Ganga and Yamuna are among the most affected rivers due to urban and industrial waste.

Pilgrims offer prayers along the banks of the Ganges River strewn with flowers offered in religious rituals and plastic bottles at the break of dawn on March 04, 2025 in Varanasi.

| Photo Credit:

Abhishek Chinnappa

Polluted water of a drain that merges into the Yamuna river near Taj Mahal, in Agra.

Encroachment

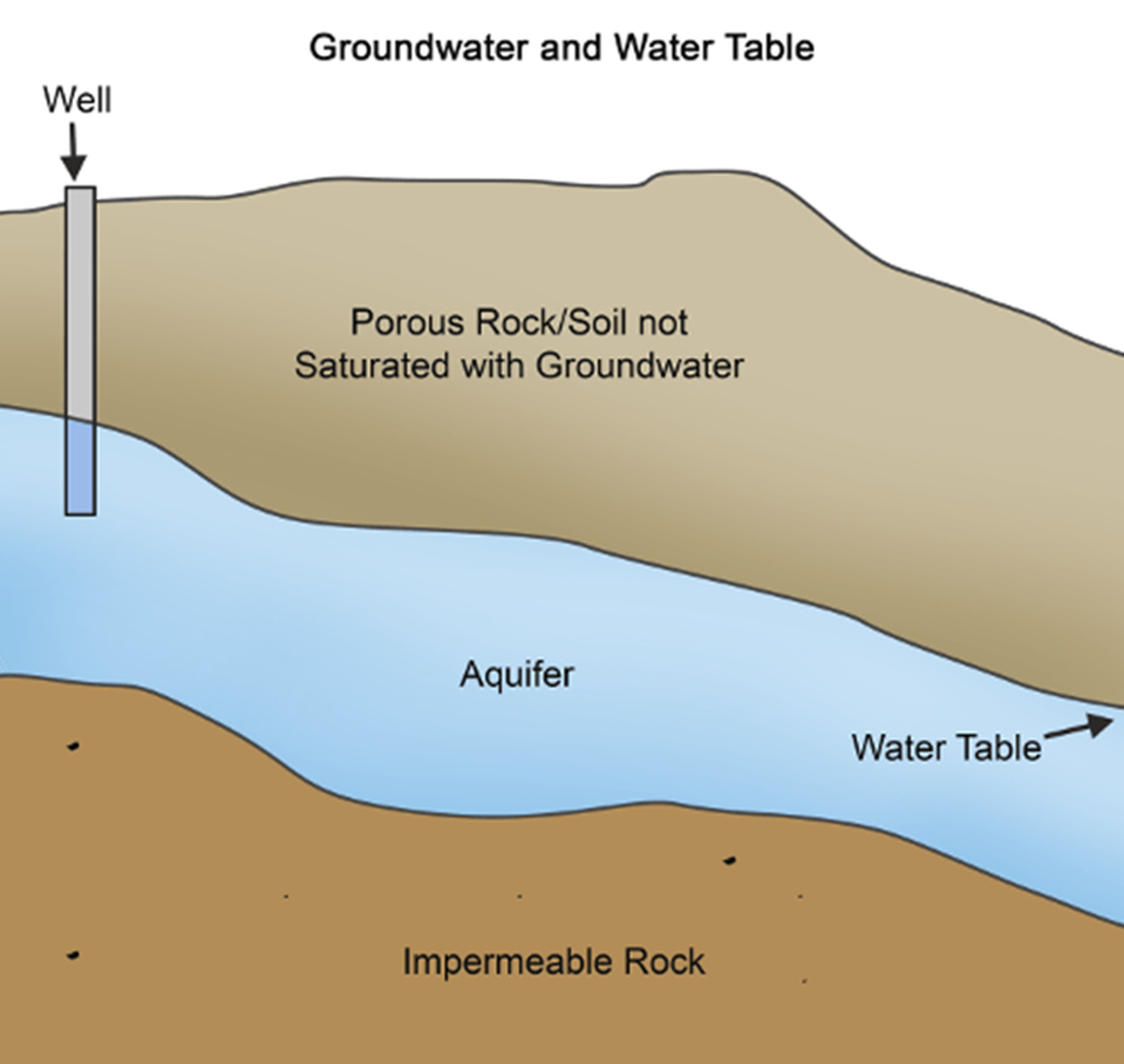

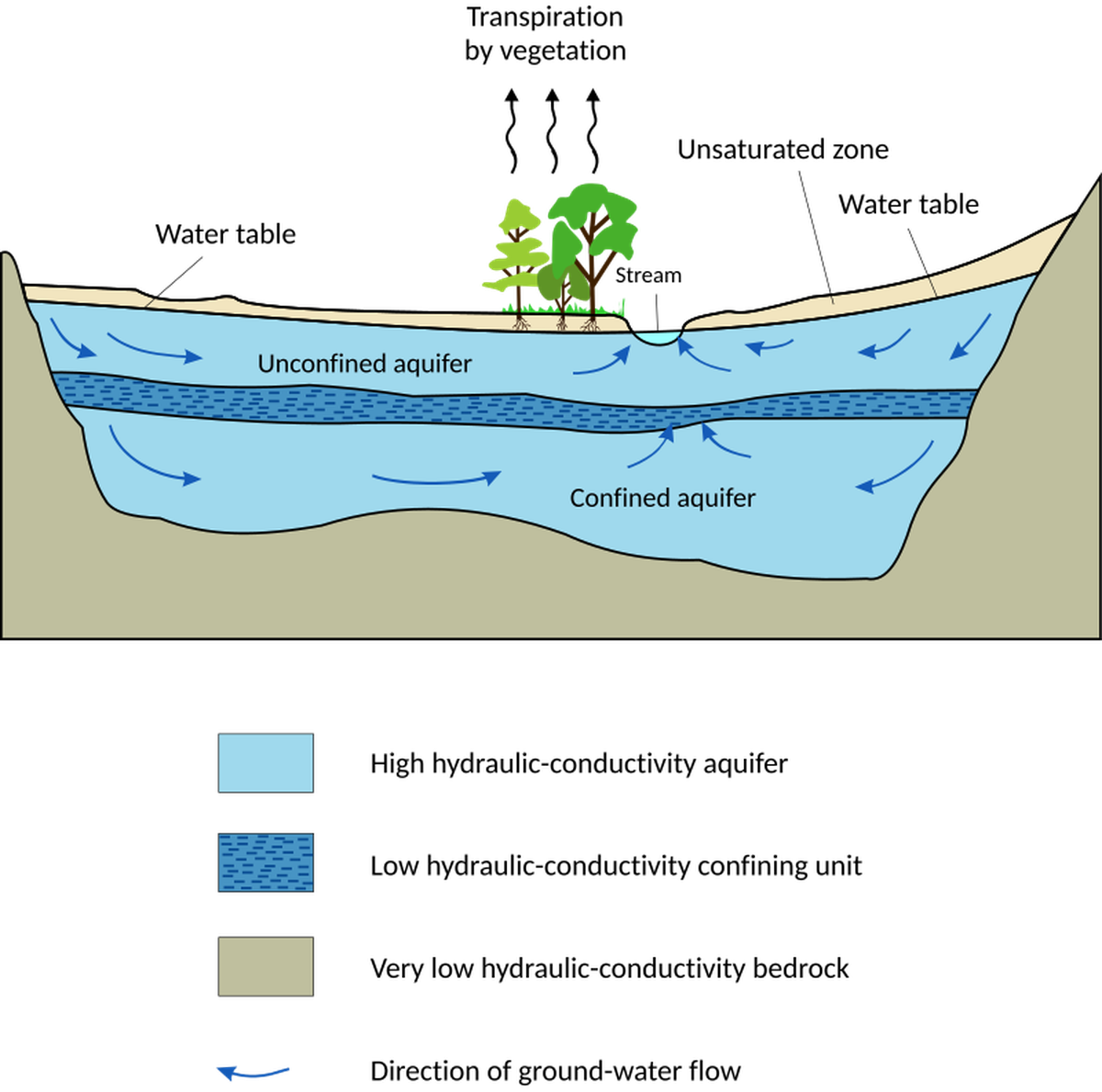

Rapid urbanisation has led to the loss of many natural lakes and ponds. Wetlands are being filled for construction, reducing groundwater recharge and increasing the risk of floods. Wetlands act as natural flood buffers, absorbing excess rainwater and reducing flood severity.

The 2015 Chennai floods are a key example—wetland loss and urban expansion worsened the impact of heavy rainfall.

Zooming in on the largest wetland in India

Sundarbans Mangrove Wetlands (West Bengal) – The largest mangrove forest in the world, covering around 10,000 sq. km (with 4,200 sq. km in India). The ecosystem faces severe threats from rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and human encroachment, endangering both biodiversity and local livelihoods.

Tourist boats in the Sundarbans.

| Photo Credit:

SHAILENDRA YASHWANT

A woman is standing in front of her house which is under water due to tidal flood in Mousuni Island, Sundarbans.

| Photo Credit:

Supratim Bhattacharjee

India has lost nearly 35% of its wetlands in the last four decades due to urbanisation and encroachment. Over 50% of wetlands in major Indian cities (including Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, and Chennai) have disappeared due to construction and land use changes.

Zooming in on Ganga

The Ganga, one of India’s most sacred and significant rivers, is also among the most polluted. High levels of faecal coliform bacteria, especially in cities like Varanasi and Kanpur, indicate severe contamination from untreated sewage and human waste. Industrial effluents, plastic waste, and urban run-off further degrade its water quality. Despite various clean-up efforts, pollution remains a major challenge, impacting both the environment and millions who rely on the river for daily needs.

Gopal Pandey, a laboratory technician checks a river water sample collected to test for faecal coliform bacteria from the Ganges River in the Swatcha Ganga Research Laboratory, a collaborative project of the Sankat Mochan Foundation, State Bank of India (SBI), the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation and the Australian High Commission for India, New Delhi, on March 05, 2025 in Varanasi, India.

| Photo Credit:

Abhishek Chinnappa

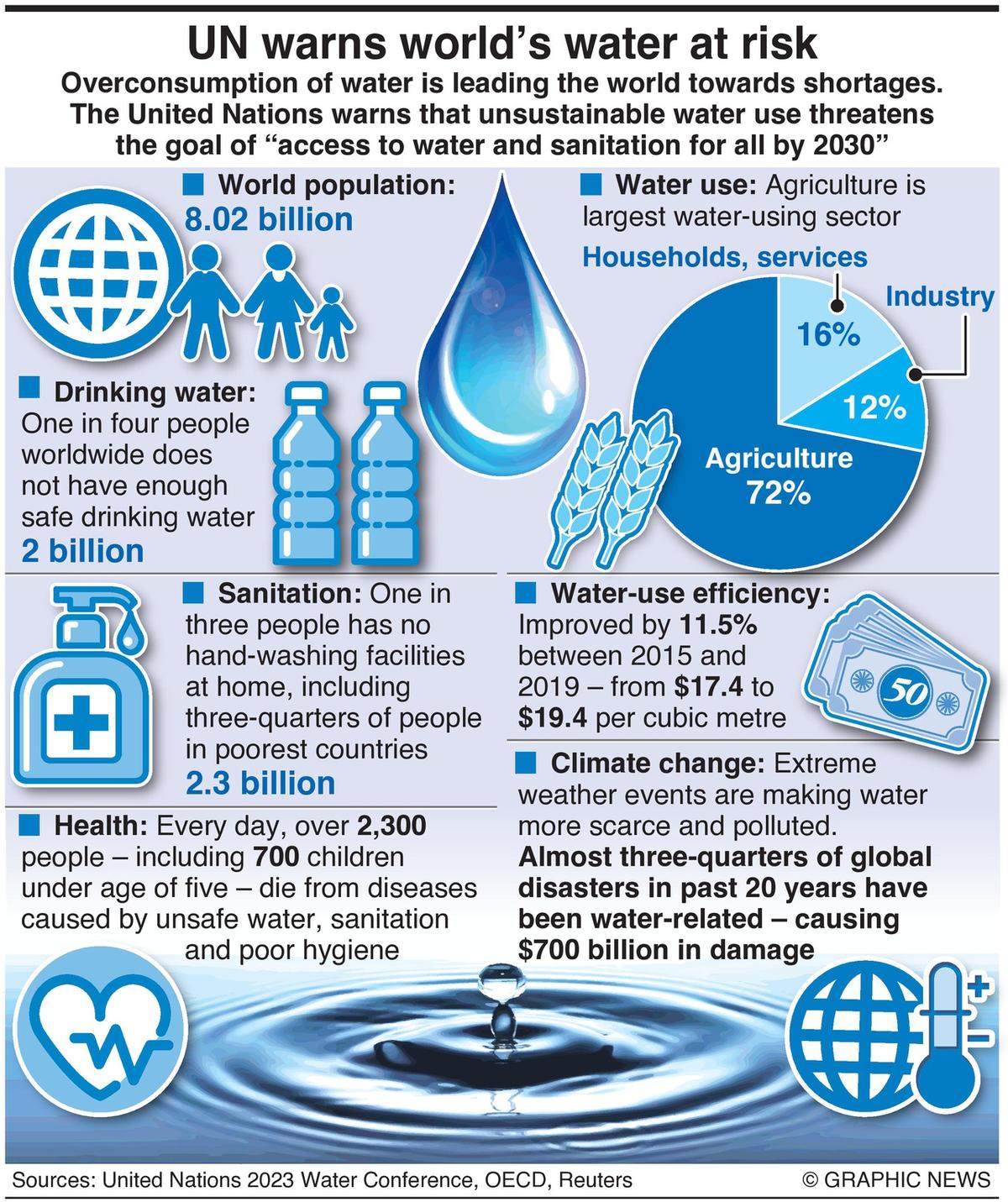

Overuse & mismanagement

Excessive damming, sand mining, and over-extraction of water have led to shrinking rivers and depleting lakes. Many traditional water bodies are drying up due to neglect, reducing their role in water conservation. Sustainable management is crucial to preserving India’s surface water resources.

Looking back into history

Water management has been an integral part of Indian civilisation for thousands of years, with advanced systems designed for storage, trade, and daily use.

Harappan Water Systems

The Great Bath of Mohenjo-Daro is one of the earliest examples of public water storage, possibly used for ritualistic purposes. The reservoirs of Dholavira in Gujarat highlight the sophisticated rainwater harvesting techniques of the Harappan civilisation.

Lothal’s Dockyard

The ancient port city of Lothal (Gujarat) had an advanced dockyard, showcasing early water management for trade. It featured a well-planned drainage system and a basin for ships, proving the importance of water in commerce.

The most scientifically built dock-yard with an inlet of its age of Lothal. It had water-locking arrangements. It was built as an artifiicial basin for sluciing ships at high tide. Vessels from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Dil mun (Bahrain) and Magen, loaded with goods, berthed there. After unloading their goods and receiving fresh supplies of water & food, these vessels returned to their countries. The ships were serviced at the dock-yard. The Harappans had built the ebb and flow of the tides before they built the dock-yard, the dockyard was built at the mouth of the river Sabarmati.

| Photo Credit:

VIJAY SONEJI

Protection and policies

To safeguard India’s surface water resources, several policies and initiatives have been implemented to promote conservation and sustainable management.

-

Wetland Conservation Rules, 2017: These rules aim to protect wetlands from encroachment, pollution, and degradation. They regulate activities that may harm these ecosystems and encourage local participation in conservation efforts.

-

National Mission for Clean Ganga (Namami Gange): Launched in 2014, this flagship program focuses on river rejuvenation, pollution control, and sustainable water management in the Ganga basin. It includes sewage treatment projects, afforestation, and biodiversity conservation.

-

Jal Shakti Abhiyan: This initiative promotes rainwater harvesting, groundwater recharge, and efficient water use across India. It focuses on water conservation efforts in both rural and urban areas to ensure long-term water security.

Wake up, before we run dry!

We worship our rivers, yet we poison them every day. 46% of India’s rivers are polluted. A nation that reveres water is turning it into a toxic wasteland.

Villagers are seen as they are heading towards the remaining water of a river to collect waters for their families domestic uses just outskirts of Kantabanji town of Balanir district of western Odisha. Maximum stream line rivers are dried out in every summer season and people always facing water scarcity in these areas.

| Photo Credit:

BISWARANJAN ROUT

Every single day, 38,000 million litres of untreated sewage flow into our rivers—pollution on a scale we cannot ignore. In Chennai alone, 250 million litres of raw waste is dumped into water bodies daily. We generate over 72,000 million litres of sewage but can treat only 32,000 million litres. The math is simple—we are drowning in our own waste.

Why? Because funding flows where public interest is loudest. While programs like Swachh Bharat and Namami Gange have tried, lack of effective implementation is killing our progress.

This isn’t a slow-moving crisis—it’s happening now. If we don’t act, water conflicts won’t be a distant threat; they will be our reality.

Published – March 22, 2025 10:30 am IST