The first time I meet Archana Trasy and her partner Pooja Chaudhri is via a beautiful pride advocacy short film on Instagram. “I always say this to Archu, you really brought colour into my life,” Chaudhri, a media consultant, says in the film, walking into an open windy terrace overlooking the Arabian Sea, perhaps hinting at the openness of their own identities. “We are in a same-sex relationship and we wear this love with a lot of pride,” says Trasy.

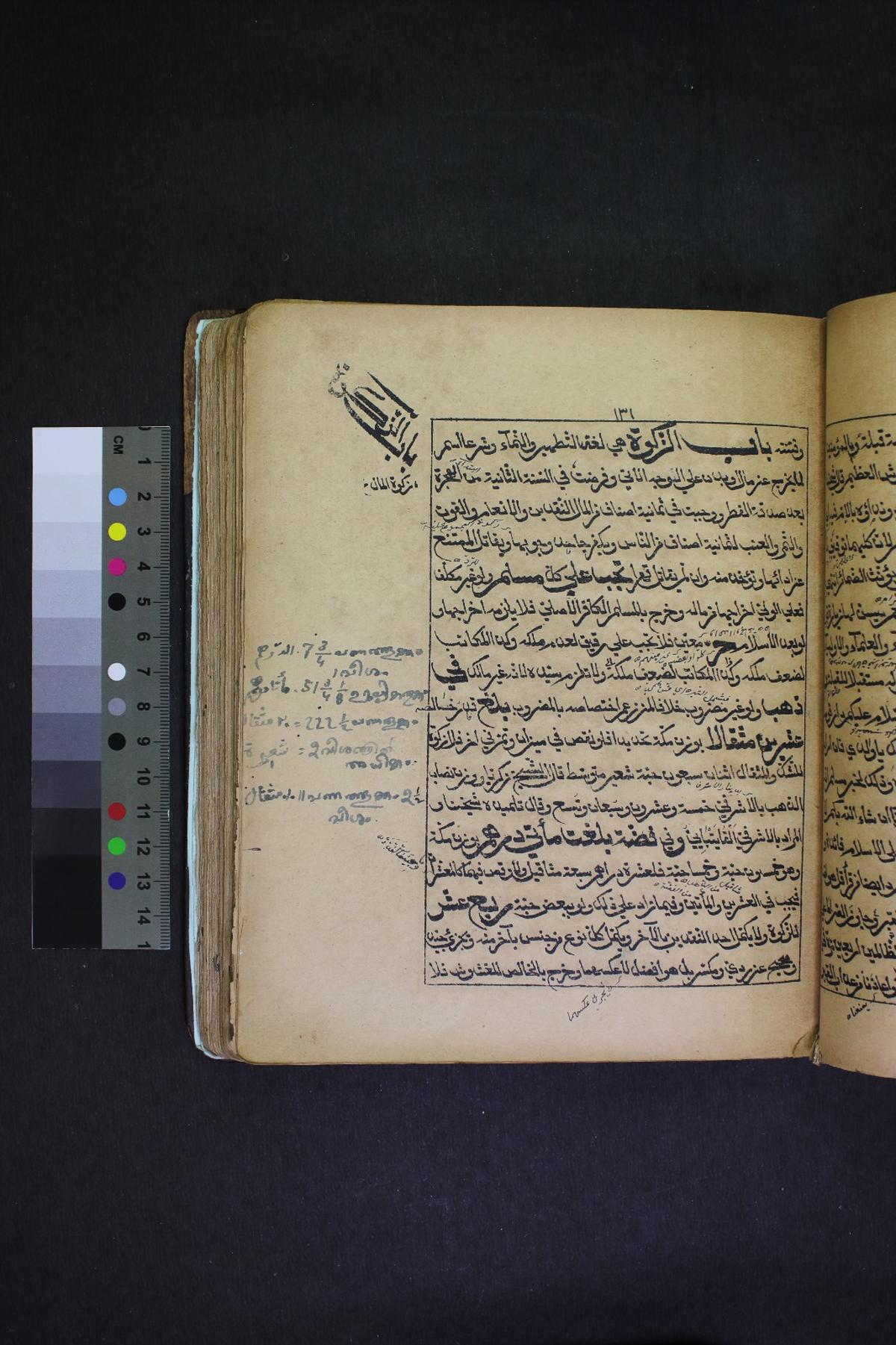

“I feel privileged to have a partner,” she tells me later. “We’ve been together for five years.” Trasy, 53, founder of an entertainment design company in Mumbai, came out at 18. Her parents were supportive though many others were not.

Archana Trasy (left) and Pooja Chaudhri

Down south in Tamil Nadu, Gita, 67, has recently moved into a senior living community with her 77-year-old partner. “Everyone thinks we are cousins and it’s best kept that way,” she says over a video call. Gita looks visibly exhausted from caring for her ailing partner. Moving here took up much of her savings, she says. “I have no support from my family because I choose to live with her. Keeping our identity hidden works best.” Gita and her partner initially lived in an apartment in a different South Indian city but the latter’s failing health made a senior living set-up with medical assistance on hand a practical choice.

Gita’s decision to hide her truth, unlike the openness celebrated by Trasy and Chaudhri, is the lived experience of many older queer persons in India, who grew up in the shadow of Section 377. Despite long battles for equal rights, they struggle to carve out a secure life without legal or institutional support.

In a landmark judgment in 2018, the Supreme Court of India decriminalised consensual same-sex relations by striking down Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. While that opened a big door for the LGBTQIA+ community, which constitutes roughly 10% of the population, another one was shut a few years down the line when the court rejected the community’s plea for marriage equality in October 2023. Same-sex couples in India also do not have the legal right to jointly adopt children as they are not recognised as eligible adoptive parents.

Marriage as a framework provides legal security in inheritance, housing and medical decisions, apart from social recognition and acceptance, the key factors behind the push for marriage equality. But it remains a contested demand among some queer activists who believe the focus should instead be on implementing existing directives and fighting to remove discrimination.

Some rights exist — such as opening a joint bank account or adding a queer partner’s name in the family ration card — but enforcement remains a challenge, say activists. The denial of these basic rights often has repercussions as people grow older or start planning their future in their late 40s and 50s. It impacts decisions around parenting, financial security, healthcare access, social inclusion, caregiving and dignity in death. Growing older as a queer person in India is fraught with problems that many take for granted in a heteronormative framework.

Finding data on the number of older queer persons in India is difficult. Surveys are hard to come by. “An online survey of more than a million queer participants in India showed that almost 40% of the participants were aged 45 years or older, with almost 30% of this group married to women and 20% hiding their gay/bisexual identities from their spouses,” notes ‘Psychological well-being of middle-aged and older queer men in India: A mixed-methods approach’, a rare study on the group by Sharma A.J. and Subramanyam M.A., published in PLOS One (2020), a peer-reviewed journal.

Hope in legislation

• Under the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017, queer persons can make a living will/advanced directive to state who can make medical decisions on their behalf.

• Devu G. Nair vs. State of Kerala case (March 2024) has extensive guidelines on police protection and habeas corpus cases involving queer couples.

• The Ministry of Home Affairs has issued advisories that give queer couples joint ration cards and rights to joint bank accounts.

• The Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India has encouraged insurance companies to offer inclusive health plans.

(Inputs from lawyer Rohin Bhatt, author of The Urban Elite v. Union Of India)

A fragile revelation

Girish, 58, a doctor’s assistant from Chennai, speaks to me on a WhatsApp audio call from a friend’s office because at home his conservative brother still doesn’t accept his sexuality. He doesn’t want to switch to video though he shares his first name. For years, his family took him to “counsellors” to cure his sexual orientation. “Now they don’t ask as long as I stay quiet; I also don’t force them to accept anything, as long as I have a place in their house,” he says. Girish would like to live independently but cannot afford it. “I no longer have a partner or the resources to be active in gay circles. I’ve accepted my life and live quietly,” he says.

For many older members of the LGBTQIA+ community, coming out remains the biggest issue. Those who manage to do so, often talk about the lack of reference points growing up. Filmmaker Sridhar Rangayan refers to that era’s impact as “permanent scars”. “Our generation has always lived under the cloud of criminality… Even now, when greater freedom is there in the cities, and the youth feel liberated, most elderly gay men live in the shadows. Hardly a few are partnered and even in these partnerships, they have to tread with caution, since there is so much pulling them apart.” Rangayan, 62, a marriage equality petitioner with his partner Saagar Gupta, 56, is co-founder of The Humsafar Trust and the annual Kashish Pride Film Festival in Mumbai.

Queer activists Saagar Gupta (left) and Sridhar Rangayan

The Seenagers, a Mumbai-based group of gay men over the age of 55, has many closeted married members. The group introduces itself as an initiative that gives “elderly gay men a safe space to connect over cups of chai”. Founder Ashok Row Kavi, among the first to openly talk about homosexuality and gay rights in India back in the 80s, says, “Many use pseudonyms at first. Once they feel safer, they share their true identities.” He warns that secrecy can lead to risky behaviours and even blackmail. “Older gay men in India often find themselves vulnerable,” says the 78-year-old.

Mental health concerns are also prevalent among the older group. “Anxiety, depression, and stress are significantly higher in the LGBTQIA+ population,” says Delhi-based psychologist and marriage equality petitioner Ankita Khanna. “For those in their 50s and 60s, these struggles are chronic, shaped by decades of secrecy. Mental health stigma intersects with the taboo around sexuality and gender, making it even harder for older individuals to seek help.”

The dearth of queer affirmative mental health specialists in India further complicates care. “When you think in terms of those catering to the ageing population, then it becomes even more of a rarity,” says Amit, 47, an LGBTQIA+ rights activist in Kolkata. He has seen a recent disturbing trend that may increase chances of elder abuse, he says.

“When the Supreme Court read down Section 377, it made it clear that only consensual acts were decriminalised, while non-consensual acts remained punishable. However, with the Bharatiya Nyaya Samhita replacing the Indian Penal Code, the government has left out any direct mention of non-consensual same-sex acts, creating a legal vacuum,” says Amit. In both online and offline spaces, he thinks this has contributed to an increase in abusive behaviour. The lack of prosecution makes the elderly more vulnerable.

“The concerns of older queer individuals were not part of the LGBTQIA+ agenda, likely because most queer activists back then weren’t older. Until one personally experiences ageing-related vulnerabilities, they may not act on them. Research on these issues is increasing, and the Varta Trust is planning a year-long qualitative study on the concerns of elderly trans and queer persons. In Varta’s mental health peer counsellor support group, for instance, efforts are being made to ensure at least 30%–40% of counsellors are over 40 or 50. For ageing queer people seeking safe spaces to live, there are the metro cities, but emerging queer networks in places like Kerala, Odisha, and Assam provide alternative options. These are places where the queer networks are young, active and thriving. However, much remains to be done to ensure that older LGBTQIA+ individuals are not forgotten, both in community initiatives and policy frameworks.”Pawan DhallQueer archivist, writer and founding member of Varta Trust

Legal hurdles with death and adoption

Even for those in secure partnerships or families, love comes with roadblocks. Dignity in death often crosses Trasy’s mind. “In medical situations, the lack of legal recognition scares me. I often worry that if I were to die, my partner wouldn’t have the legal right to make decisions for me or to claim my body. I want to live and die with dignity, and I’d prefer my partner to have the authority to act on my wishes,” she says.

Documentary filmmaker Pracheta Sharma, 44, is parent to a six-year-old girl she adopted in 2020, around the same time she met her partner Mamta Saraf. She talks about how India’s adoption laws and the lack of marriage equality adversely impacts their family structure. “Within the adoption laws, you are not allowed to declare anybody else as a legal guardian if they’re not from your family [blood relation]. One parent has to adopt and the other remains in the shadows. I think it’s a highly discriminatory space in a setup that has decided to be progressive. If I was with a man in this equation and I wanted a family, a civil marriage is all it would take, and he would automatically become the other parent. But with a same-sex partner I can’t do that,” says Sharma.

Among the small changes that Pracheta Sharma (left) and Mamta Saraf have managed to make around them is the introduction of gender-neutral ‘parent’ ID cards in their daughter’s school in Mumbai, replacing the traditional ‘father’ and ‘mother’ cards.

Not being a legal guardian in the adoption papers translates into several problems for Saraf, 46, who has no rights beyond social acceptance. Travelling alone with the child can create issues and even making an investment or insurance in her name needs to be done through circuitous routes, setting up problems for the future. Saraf and Sharma are open about their relationship (it helps to live in cosmopolitan Mumbai) with their families, housing society, and their child’s school. But challenges remain. The couple is currently working on options to secure their child’s future.

In the absence of marriage equality, some queer couples create a living will, or insurance nominations, or social contracts with family and friends to ensure their wishes are respected. “Since the system doesn’t give us rights, queer people must constantly safeguard their own,” says Saraf. “Making a will in your 40s isn’t enough; you have to ensure your partner isn’t sidelined later.”

There are couples who find protection through business partnerships. “Our production company, Solaris Pictures, ensures shared assets,” says Rangayan.

There is a constant need for jugaad if you are a queer person, says Khanna, 41, who lives with her partner, psychiatrist Kavita Arora, 51. In their eight years of living together, the mental health practitioners have faced several “minor dents”, be it in the process of opening a joint bank account or applying for a swimming pass in their apartment.

Maya Sharma, 70, says she and her older queer female friends often think of finding places to stay together instead of having to fit into heteronormative spaces. Unlike in western countries, where there is a push towards senior living communities catering to queer people or more acceptance within regular senior communities, India has a long way to go.

Writer and queer activist Maya Sharma

Sharma, who runs the Vadodara-based Vikalp, which works with marginalised queer women and transpersons, says she finds the senior living communities in Gujarat limiting. “The way we have been moulded because of our queer identities makes it hard for us to fit into the heteronormative environment of an old-age home. Secondly, many of these places are religion-oriented and many of us have friends and lovers from different religions and castes. So these religion-centric old-age homes are frightening to us,” she says.

Finding chosen families

In the absence of formal support structures, many depend on chosen families. “I have a network of friends who have been with me since college. They are my family,” says Iggy, 51, a production designer in Mumbai. Iggy recently moved from Goa with her partner of 12 years to give her dogs better medical care. She tells me how, while coming out in her 30s, she discovered a “whole new world” of queer individuals. There were groups such as Labia and Gay Bombay in the early 2000s; the queer-run store Azad Bazaar, where the balcony became a community hub, with free coffee; and Gulabi Adda, which held monthly meetup parties that brought a sense of belonging and lifelong friendships.

“It was almost like a renaissance where more queers were out to me visually than they are today,” Iggy says. It helped to create a community that Iggy feels has shifted to online spaces for younger queer people today. Activists believe this may leave out the older lot that is not digitally savvy and unable to access information on resources such as support groups, therapists, sexual health services or simply finding spaces to hang out.

Ageing and transgender persons

With her big bindi, gorgeously draped saris and bold voice, Ranjita Sinha is a fiery presence in Kolkata’s transgender community. She runs South Asia’s first government-run trans shelter home, Garima Grih. “Transgender individuals face unique medical, social, and legal challenges that cannot be conflated with those of the wider LGBTQIA+ community,” she asserts. Despite the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, and the Ayushman Bharat TG Plus card which promises medical aid, Sinha says access to healthcare remains tough. “No one wants to go to government hospitals. There is no mindset change in the doctors there. Trained doctors are only in the big hospitals, and how many older transgenders can afford the ₹1,000-₹2,000 fees in those facilities?”

There have been promises from the government to establish old-age homes for transgender individuals but nothing has materialised yet. “There needs to be an ecosystem for older trans people. They face huge issues — mental health, post-sex reassignment surgery complications, and sometimes complications from quack treatments. But lack of access to healthcare or family support leaves them in a tough situation,” says Sinha.

That said, Maya Sharma points to the strong support among female queer collectives that are different from the worlds gay men inhabit, perhaps because women’s concerns are different when it comes to stigma and HIV-related issues. They often help trans-masculine and lesbian women from smaller towns who have fled to escape persecution or forced marriages. “A lot of us older women have created advocacy collectives such as Vikalp, Nazariya, or Sappho, and we help them out. But we can’t always help in day-to-day living. That kind of acceptance requires institutional support, which is lacking,” she says.

When it comes to older transwomen, the ‘jamaat’ takes care of them. “It’s their chosen family,” says Jaya, transwoman, trans-rights activist and general manager at Sahodaran, a queer rights NGO in Chennai. “The ‘jamaat’ system is a beautiful tradition in Indian transgender communities, where younger transwomen are adopted by older transwomen into a chosen family. As a result, very few older transwomen are homeless or in shelters as most are part of a ‘jamaat’. But even then problems persist,” she says.

Jaya, trans-rights activist and general manager at Sahodaran, a queer rights NGO in Chennai.

Healthcare needs become more pronounced with age. Jaya says that older transgender individuals, aged 70 and above, are hardly visible in the community. She hints at a lack of medical care and good health habits as many fall into alcohol abuse. “Many post-operative trans people report health issues such as back ache and knee pain, likely due to weight issues,” she adds. The lack of doctors trained and sensitised in transgender healthcare is a big worry. Sahodaran is working to change this through awareness programmes among doctors, says Jaya.

In Tamil Nadu, the Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme offers partial cover for medical treatment of transgenders but it works in only a few hospitals such as the Aadhi Parasakthi Hospital in Chennai, says Jaya. The Tamil Nadu government also has a pension scheme that provides a monthly allowance of ₹1,000 to transgender people over the age of 40, who are unable to earn a livelihood.

Many activists agree that the landscape is evolving. Khanna says that a number of people “came out to their families during the marriage equality fight” as it was being livestreamed on national television, resulting in these conversations coming into the mainstream. She admires how courts have provided support and protection to marginalised queer couples across India in the last couple of years. “People with privilege, and banks, organisations and authorities, need to come up with such explicit support to help those without privilege access it. Then, it can be truly empowering.”

The writer is a freelance journalist and the co-author of ‘Rethink Ageing’ (2022).

Published – March 28, 2025 01:39 pm IST