Sitting down to write about finishing my first 5K feels as exciting as lacing up my running shoes for the Dubai Run 2025. The journalist in me wondered how so many of us had descended upon Sheikh Zayed Road for the world’s largest free community run.

There were 3,07,000 of us (yes, you read that right!).

Families, fitness enthusiasts, and runners of all ages and abilities turned the Dubai Fitness Challenge’s flagship event into a spectacle on a chilly Sunday morning in November last year. A parade of police supercars led the way for the 5K (through Downtown Dubai before finishing near Dubai Mall) and 10K (passing the Museum of the Future, Dubai Water Canal, and Burj Khalifa before finishing at Dubai International Financial Centre Gate Building) runs.

The aerial paramotors doing the rounds in perfect synchrony had the crowd point their mobile phones towards the sky to capture a picture or two.

The DJ’s groovy beats and celebrity MCs Kris Fade and Katie Overy kept spirits high as we arrived at the starting line.

Just as doubt crept in whether my two-week training regime was going to be enough, a reassuring voice echoed from a nearby speaker: “A big round of applause… pat yourself on the back for coming out for the run this morning.”

After leaving my hotel at 6am and ambling towards the starting line for around an hour, it was finally time to walk the talk and begin running. A metro train — brimming with more runners, most of them in their sponsored blue jerseys, waiting to join the fun — zoomed past as I started the run near the Museum of the Future.

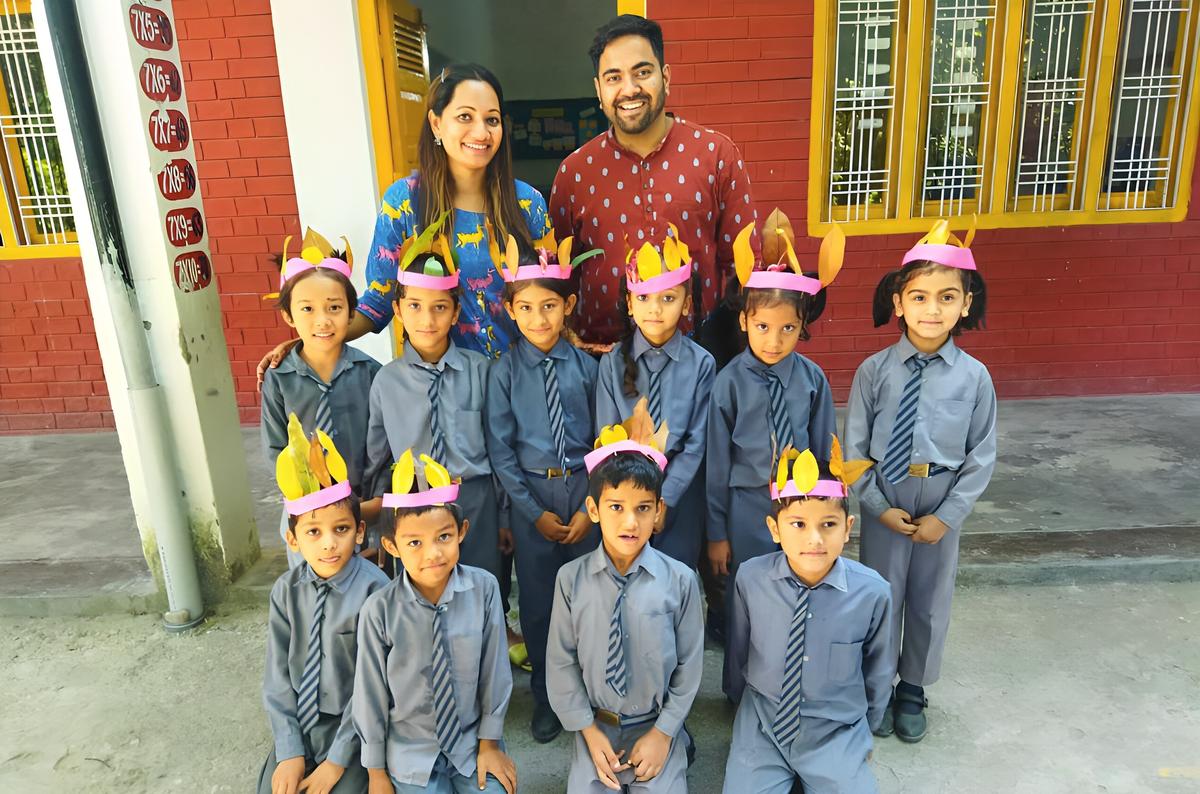

The run had 3,07,000 people participating

| Photo Credit:

Sankar Narayanan E H

Countless metro trains passed by me the same way and I can safely say that my steady running pace didn’t alarm the speed cameras at Sheikh Zayed Road one bit.

I should have also thought twice before choosing to record a running commentary on my phone. For I could hardly string two sentences together with all the gasping and sweating. I’m quite proud of the Instagram reel I managed to edit out of that raw footage though.

I had made up my mind to alternate between “excuse me” and “on your left” for every overtake I managed (yes, I was attempting to emulate Steve Rogers, aka Captain America, running past Sam Wilson).

It definitely helped me — and many others, I presume — that there was no dearth of encouragement along the way, as volunteers, fellow runners, live performers (in the form of marching bands, stilt walkers and circus acts) cheered one and all.

The DJ’s groovy beats and celebrity MCs Kris Fade and Katie Overy added to the experience

| Photo Credit:

Sankar Narayanan E H

The dopamine rush trounced the exhaustion of roaming around Dubai for the past three days; my tired feet found new energy for the final leg as I sprinted the last 100m to finish the race on a mental and physical high.

Hugs were exchanged, pictures were clicked, and happiness was the overwhelming theme as I took a moment to soak in my small yet proud achievement. Just like how I didn’t write this piece in one sitting, I took a couple of breathers while completing my first 5K in around 40 minutes.

Maybe I wouldn’t take as many water breaks and selfie pitstops on my first 10K. That’s for another day!

The writer was in Dubai at the invitation of the Dubai Department of Economy and Tourism.