Every winter, a small miracle takes place across the Indian sky. High above the snow peaks of the Himalayas, at altitudes where even planes struggle to breathe, flocks of bar-headed geese glide southward from the frozen lakes of Central Asia. They descend into the wetlands of India (the Ganga plains) honking softly as they rest on the waters that have awaited them since Vedic times. This is the hamsa of Indian imagination, the bird of Saraswati, the emblem of wisdom, purity, and transcendence.

The bar-headed goose (hansa) is a key cultural symbol of India, along with other waterfowl such as the sarus crane (krauncha), ruddy shelduck (chakravaka) and crane (baga, bagula). This list excludes the swan (raj-hansa), which is European, not Indian. But somewhere in the last two centuries, the Indian goose was eclipsed.

In colonial translations, it was transformed into a European swan, a bird that never flew over the Himalayas, never nested in Ladakh, never knew our monsoons. The goose carved in stone on temple walls was ignored and everyone paid attention to swans appearing next to Shakuntala, transforming her into the Greek Leda.

Europeanising the sun bird

The hansa is the Anser indicus. It was a hardy, intelligent migratory bird that embodied the rhythm of India’s seasons. It bred in Central Asia in the summer and through the monsoon, returning to India in winter, in time to eat the lotus fruit, following the same paths that traders, monks and, perhaps, even the Indo-Aryans once followed thousands of years ago. The Vedas speak of the hamsa as the “sun-bird”, the messenger of dawn, the soul that moves between the mortal and immortal realms. In the Upanishads, it becomes a metaphor for the liberated soul — the paramahamsa, one who rises above worldly waters.

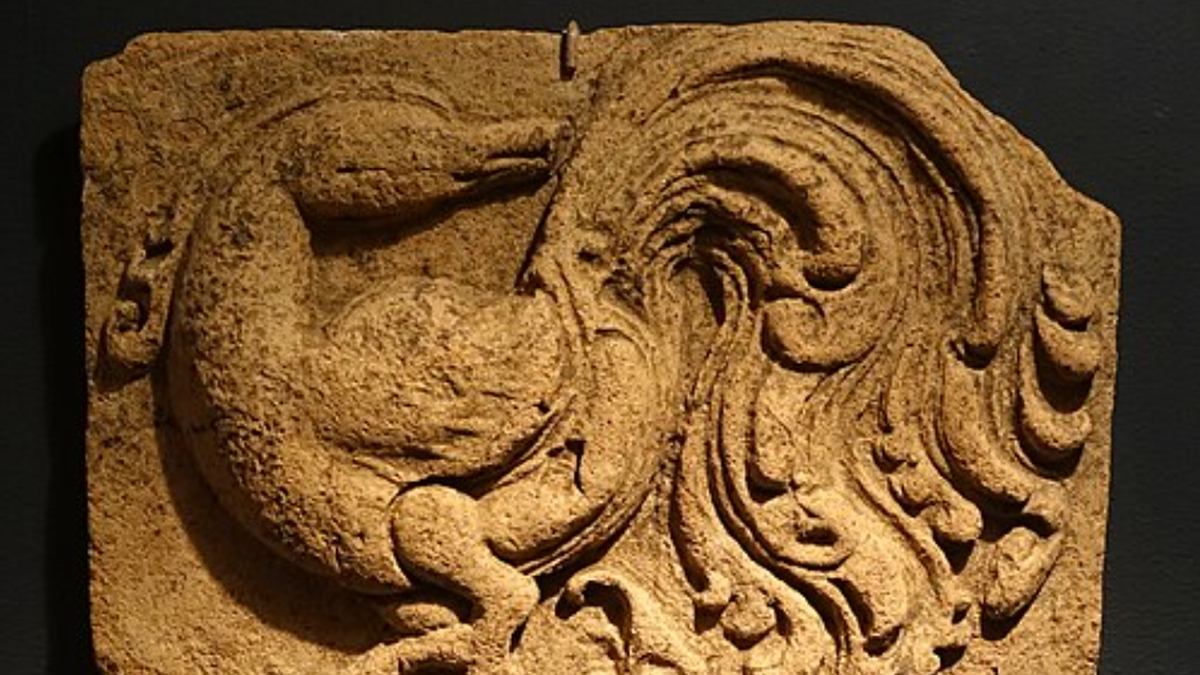

In art and sculpture, friezes of 12th-century temples at Belur, Khajuraho, and Konark show the bird carved beside Saraswati, with a blunt beak, rounded body, and webbed feet. This was India’s own sacred bird — born of her rivers, not borrowed from Europe’s ponds.

When Europeans began translating Sanskrit in the 18th and 19th centuries, they encountered the word hansa. To them, it resembled the swan of their myths — the pure white bird form taken by Zeus to seduce Leda, or the swans of German folktales. So Saraswati’s companion was Europeanised and deemed more elegant than the ugly goose. The swan was like a ballet dancer; the goose was the squat Indian nautch girl.

A painting showing Brahma, the four-headed deity, with Saraswati in his lap, riding on his vahana, the hamsa.

| Photo Credit:

WikiCommons

The change seemed innocent, even poetic. But this mistranslation was not without consequence. Once the swan entered our art books and textbooks, the Indian goose vanished. Painters in British India, raised on European imagery, began to draw long-necked swans on temple posters. School books described Saraswati riding a swan. Even modern temples began installing swan imagery on signboards and calendars.

Over time, the bar-headed goose — once the bird of the Himalayas — was exiled from its own mythology. This was colonisation of imagination. We rejected the bird that actually flew over our skies in favour of one imported through colonial eyes. The swan became Sanskritised, while the goose was forgotten.

Erasing geography from faith

In the Sanskrit poem Hansa-sandesha (The Goose Messenger), Rama sends a hamsa to carry his message to Sita across the sky. She is equated with the lotus flower blooming through the monsoon waiting for the goose to arrive. By the time it does, the rains are over. It is autumn (śarad). The lotus has shed its petals and the fruit is ready for consumption. Saraswati is worshipped, and the season of knowledge begins. In poems such as these the rhythm of nature and the rhythm of myth were once one.

Modern education separates zoology from literature. Children are not told that Saraswati’s goose is among the most extraordinary creatures on earth. It flies over the Himalayas at heights above 25,000ft, where oxygen is one-third of normal levels. Scientists still marvel at its lungs and blood chemistry. It flies at night, in formation, gliding on thin air, carrying no luggage except memory. Its annual journey, from the salt lakes of Tibet to the flooded plains of India, has continued unbroken for millennia. To call the hansa a swan is to erase geography from faith.

The orthodox Hindu who insists on painting Saraswati on a swan repeats a colonial error, mistaking imported iconography for authenticity. But the temples tell a different story. On their 800-year-old walls, the hamsa looks like what it truly is — a goose, not a swan.

Devdutt Pattanaik is the author of 50 books on mythology, art and culture.

Published – January 17, 2026 02:08 pm IST