Truthfully, I was rather intimidated by Geeta Doctor. For she was not a traditional person. Geeta was, I think, a non-believer. She seemed to critique different art expressions with what you might call ‘a clean slate’. She was happy to learn, to observe, comment on all art forms — literary and performative, visual and tactile, Indian or world art, not burdened by the rules thereof. Simply as ‘the other’.

She was watchful and witty, a giggle lurking behind her smile, ready to unbalance you. I was often tongue-tied. (In fact, ever since I was asked to write this tribute, I have been picturing her laughing at the choice.) But that was till I was on the other side, as it were. Once I got to know her, I shared in the amusement as we took on the dance scene like buddies, if I may say so in her absence. I wouldn’t dare in her presence!

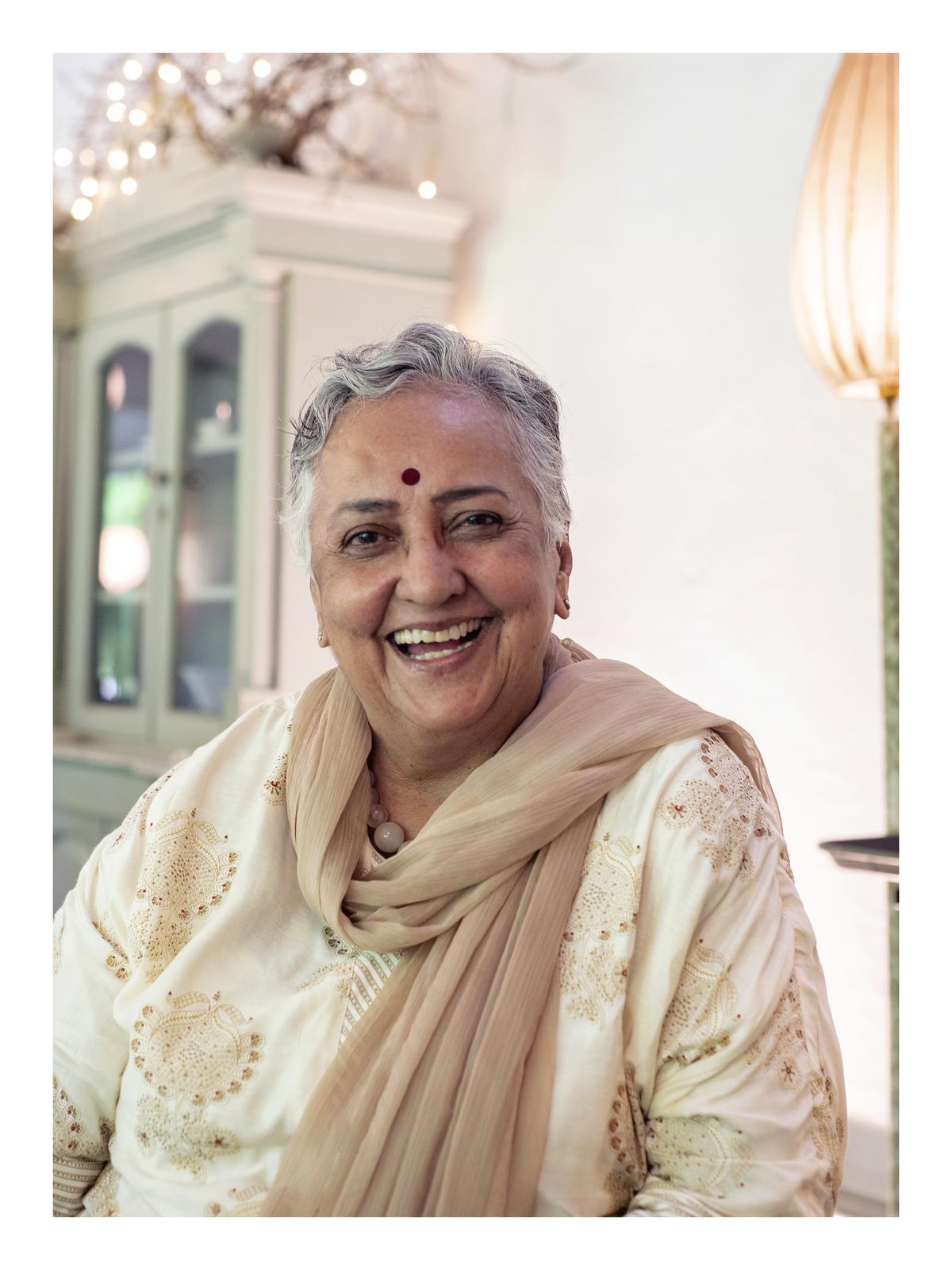

‘She was witty, a giggle lurking behind her smile, ready to unbalance you’

| Photo Credit:

Mala Mukerjee

Geeta read (and wrote) voraciously, and in the early ‘70s, she was present in her role as journalist, with a ringside seat, at a host of art movements that then emerged in Chennai. Writing a review of visual artist S.G. Vasudev’s exhibition called Vriksha in 2010, she recalled the many layered world of the ‘60s, when Vasudev and a group of artists set up the self-contained Cholamandal Artists’ Village. “It’s been described as a Village by the Sea,” she wrote. “It was in a way an epic undertaking, the old man-teacher-friend and preceptor, [founder] Paniker leading his band of faithful to make a mark for themselves in what was then a wilderness.”

Read Geeta Doctor’s words for The Hindu

This was also when I first met Geeta — when Vasudev and his now deceased wife Arnawaz, a fine artist, invited me to dance on the sands outside their new home. A performance was always followed by a discussion over a simple meal and drinks. Such a vital act, when an exchange of ideas helped in understanding our own arts and the need of the time.

A bohemian spirit

Geeta began working as a journalist in Mumbai in the 1970s, for publications such as Freedom First, a liberal monthly, and Parsiana, the Parsi magazine that shut last October. She helped start Inside Outside, India’s first design and architectural magazine. She moved to Chennai in the 1980s and wrote for many other publications, including The Hindu.

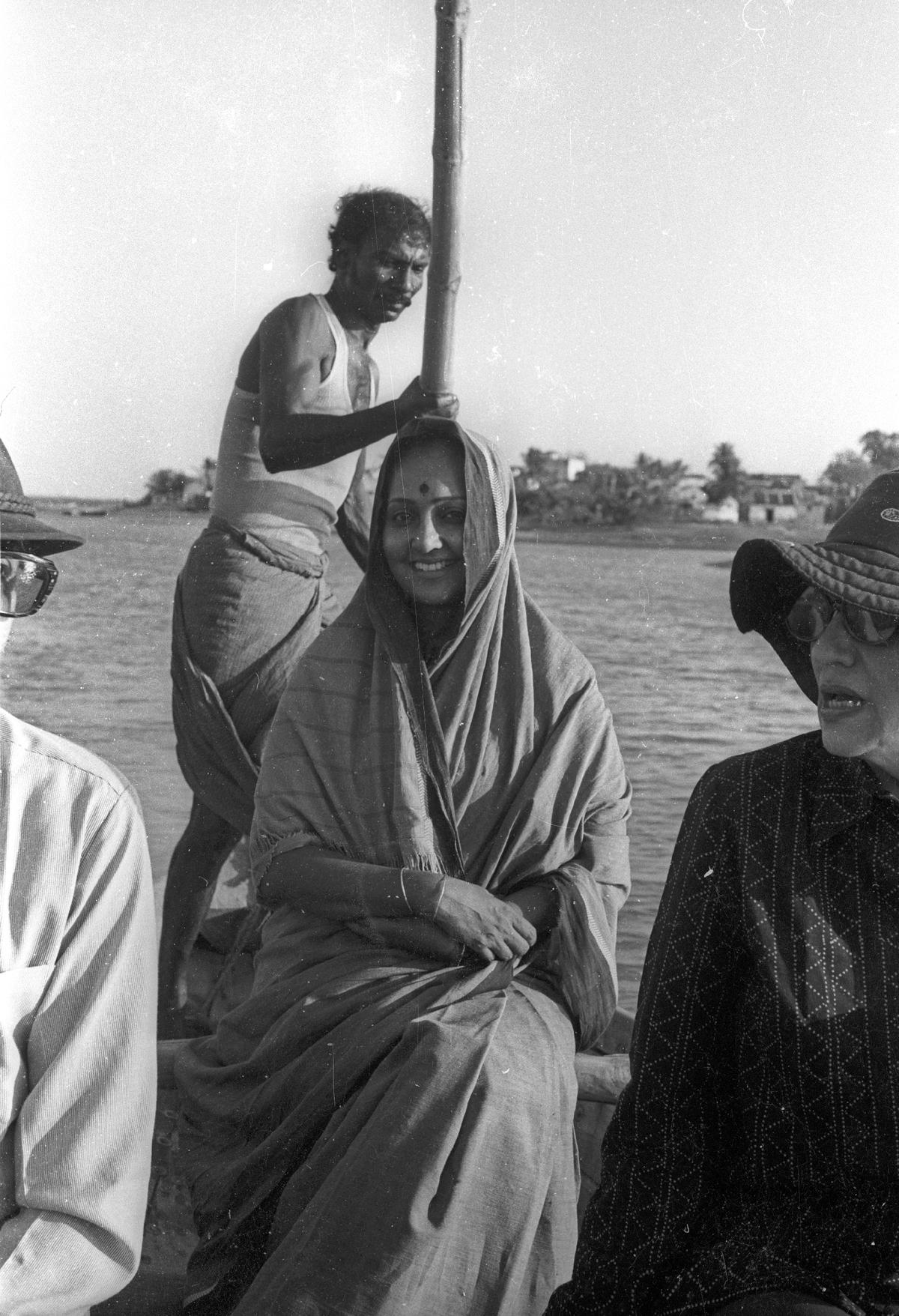

Geeta Doctor, when she had taken artist Jehangir Sabavala to Pulicat Lake

| Photo Credit:

Mala Mukerjee

A few days ago, Meenakshi, her daughter, shared some of Geeta’s writings with me that gave me an understanding of the range of subjects she reviewed. Even the headlines of the articles reflected the happy nature of one who seemed pleased to have walked with that book, that performance, that exhibition awhile.

For instance, writing about the food memoir A Bite in Time: Cooking with Memories, she remarked that it “mirrors the larger-than-life personality of Tanya Mendonsa’s invitation to take a bite of her life. Her real talent, as any bohemian spirit who has lived in Paris in the second half of the 20th century will recognise, is to be a flâneur, loosely translated it means just floating above the ground in a state of permanent enjoyment”. To me, Geeta was also a flâneur. Her own nature was reflected time and again in her reviews of others. And so we got to know her.

Geeta Doctor at Dhanushkodi

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

In December 2016, she wrote passionately about dancer and choreographer Astad Deboo. “Does he remember it as I do, the short series of six movements in which Astad trampled upon the canvas of contemporary dance in India and laid it wide open to different interpretations? Did he actually feel the pain when he slit his arms open with a blade and allowed the blood to drip? Or later, in what became a showstopper moment, contort his lithe body, so that his tongue became part of the performance. He licked the floor of his stage as though it were his most beloved other. The floor. The stage. The dancer. The audience. We became one with the performance. Astad Deboo became contemporary dance.”

Then she stated her non-partisan, broad outlook on society: “He could be a Parsi at home, a Christian at the school taught by Jesuit priests, and a student of Islamic traditions because of the Kathak dance teacher. The influences that he imbibed included that of the Bengali families, the Biharis and South Indians, all of whom enriched his idea not just of who he was but what being an Indian might be.”

It was pitch-perfect. Even now, I can let out a cry of joy at that line describing what it is to be truly Indian. Penned by a writer and critic who was born in India, but grew up in France, Sweden, Switzerland and Pakistan, following her father who was in the Indian Foreign Service.

One who spoke from her heart

Geeta, an octogenarian who presided over a four-generation family of strong women, often talked about how she loved food, laughter, and the company of strangers she met on her travels. Glimpses could be seen in her reviews.

‘Geeta loved food, laughter, and the company of strangers she met on her travels’

| Photo Credit:

Mala Mukerjee

In 2005, she could not contain her glee after she visited Malaysia to watch Kuala Lumpur-based choreographer and classical Bharatanatyam dancer Ramli bin Ibrahim. “Ramli follows in the tradition set by a Ram Gopal or even an Uday Shankar in taking the heroic moment by the hand and treading the path that is often so dangerous between becoming too exotic or too enchanted with his own sensuality. By insisting that it is a tribute to Odissi, perhaps, what he is also exploring is this very same appeal to the gorgeousness of Odissi that surrenders to the feminine in all its manifestations of desire.”

Months before she was diagnosed with a terminal disease, she wrote about Marghazhi and the people she lived among. Although inadvertently, I believe few have summed up the season so succinctly as Geeta did in her review of the book The Tamils: A Portrait of a Community. “It’s that time of the year when the invisible call of ‘The Season’ fills the air around Chennai inviting multitudes from distant lands. There is an almost imperceptible hum of the Tamil heartbeat written on the wind… that speak of a fabled past that finds expression in music and dance at different venues. In every generation, a scholar reaches into these storied depths and finds a way through the tangled roots… It makes Nirmala Lakshman’s extraordinarily vivid treatise on The Tamils doubly interesting.”

For me, Geeta’s was that independent outside-the-theatre- of-the-arts voice that spoke directly from the heart. It was a democratic voice. It held in it the echoes of a worldview that could see the connections and almost imperceptibly rejoice in them. She was not partisan; she did not beat about the bush. And for some of us, who recognised this, she will not be replicated. She will be missed. May she rest in peace.

The writer is a Bharatanatyam dancer and choreographer, and the former director of Kalakshetra in Chennai.

Published – January 08, 2026 01:28 pm IST