The origin of the caste system does not lie in religious ideas of purity and pollution, racial differences, tribal or Harappan customs — or even the British census, as recent social media commentary would suggest. It lies in ancient political contingencies and economic circumstances.

The earliest mention of a four-tiered hierarchy occurs in the Purusha Sukta of the Rigveda. But it is commonly accepted that this is a late book, and that the Purusha Sukta is a later insertion. There is no mention of the shudra in the Rigveda outside of the Purusha Sukta. There are only doubtful and rare occurrences of even ‘brahmana’ as a social category. Therefore, one can agree with Stephanie W. Jamison and Joel P. Brereton in their 2014 translation of The Rigveda, that in the earliest religious poetry of India, the caste system is embryonic.

The Rigveda : The Earliest Religious Poetry of India

But how did that embryo come to be? Studies by scholars Michael Witzel (The Realm of the Kuru) and Thennilapuram Mahadevan (The Rsi Index of the Vedic Anukramani System and Pravara Lists: Toward a Prehistory of the Brahmans) provide the keenest insight.

To recount Witzel’s arguments briefly, the tribe of the Kurus became predominant after the Battle of the Ten Kings or Dasrajna mentioned in the Rigveda. After the battle, the “geographical centre of the Vedic civilization” moved eastwards from Punjab to Kurukshetra, the land lying between rivers Sarasvati and Drishadvati, about 175 kilometres northwest of New Delhi. (This region would later come to be subsumed under the term Aryavarta, defined as being the region between the Himalayas and the Vindhyas, and to the east of where river Saraswati disappears and west of the Kalaka forest, which is supposed to have been at the confluence of the Ganga and Yamuna.)

As they consolidated their power, the Kurus felt the need for a unified canon, drawing on the sacrificial hymns of their own tribe as well as defeated tribes. The last hymn of the Rigveda is about unity. It says: “Come together, speak together; together let your thoughts agree…”

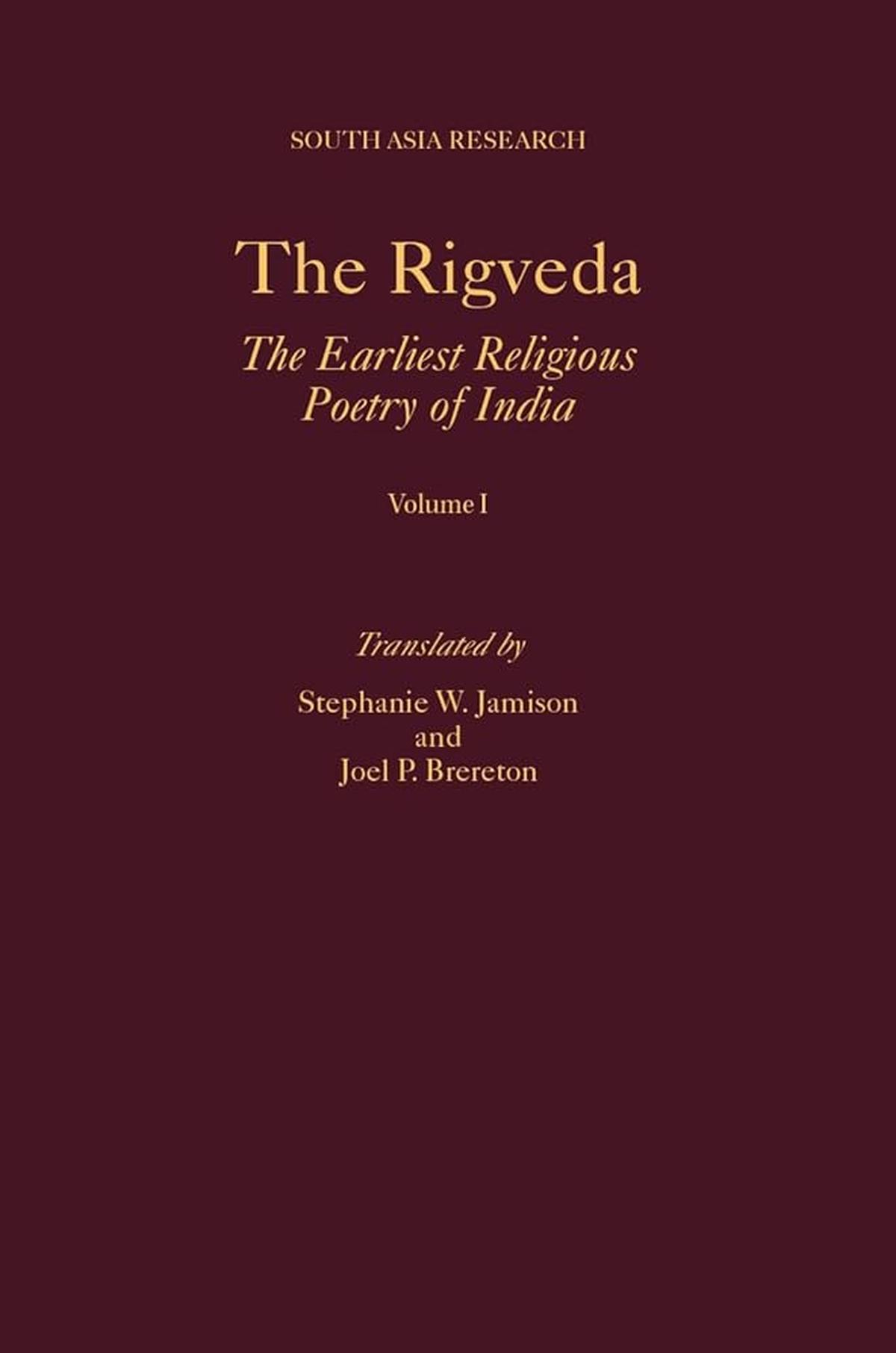

Rigveda bundles, with illustrations from each of the sections of the Veda. On display at the Saraswati Mahal Library in Tanjore.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Until this happened, around 1000 BCE, writes Witzel, “the Rigvedic hymns were held as ‘personal or clan property’”. When a common canon was made out of these collections, writes Mahadevan, the families that were once in charge of their own hymnal traditions became the backbone of a ‘pan-Vedic agency to sing a pan-Vedic corpus’. There being no writing at this time, they were now an ‘oral agency’ carrying forward a common tradition, now ‘bound into a biological body’ through new rules regulating marriages among them.

The first ‘caste’ takes shape

As Mahadevan tells it, each of those who had a collection of family songs was now called a gotra. The new rules were that marriages must not occur within the same gotra (exogamy), but must occur within the 50-odd gotras (endogamy), thus creating ‘One, Out of Many’, “the ‘caste’ of Brahmans”. The brahmanas are thus the first and perhaps the only real ‘varna/caste’ to be formed at a particular time and place, with enormous implications for the future.

The ‘ksatriya’ or the warrior/ruler caste will be mostly decided de facto: those who manage to get and keep power are regarded as ksatriyas. Historian D.D. Kosambi once wrote: “Don’t be misled by the Indian Ksatriya caste, which was oftener than not a Brahmanical fiction.” Those who do not fall into either of these categories are considered ‘vaisya’ or common folk — the residual category of the Arya community.

In the following centuries, those who were outside the Arya culture, but served the Arya as domestic workers or as farm labourers, were accommodated within the system as low-status ‘shudra’. Those who were outside of all four categories, such as the tribes who lived in the forests, were regarded as ‘outcastes’. But this fully fleshed-out varna-jati system will take time to develop, being dependent on the speed with which agriculture and, therefore, the need to engage non-family labour, took off.

An engraving from 1872 of brahmana men learning

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Many things follow from this. One, the caste system did not arise out of a purity-pollution cline; nowhere in the Rigveda or other samhitas is it suggested that there is a hierarchy of purity among the brahmanas, rajanya and the vis or vaisya. Two, it did not arise out of differences in eating habits; the idea of vegetarianism originated centuries later with the ascetic sramana traditions such as Jainism and Buddhism in Greater Magadha, which lies to the east of Aryavarta.

Three, it had little to do with race or ethnicity to begin with; the three varnas were all considered Arya. Four, the idea of a varna system did not spread from a pre-Aryan or Harappan Civilization. And five, it was not brought to India by the Steppe pastoralists, who called themselves Arya. It was made in India, and ideas such as purity and pollution were justificatory accruals that occurred centuries later.

Varanasi was important for those on both sides of the debate over varna: brahmanas and sramanas

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The trigger for the beginning of the caste system was the need of a victorious kingdom to have a unified religion and a priesthood to administer it. The best model that fits this evidence is that of a universal ‘Homo Opportunisticus’, and not an Indian ‘Homo Hierarchicus’ which, according to sociologist Louis Dumont, represents a cultural predilection for hierarchy. Given the opportunity, political and economic man will create a system of belief and along with it, a social system, to perpetuate his status and power.

What began as an embryonic scheme in the Rigveda bloomed into a full-fledged system in the later brahmana texts when settled agriculture began to take off. These texts elevated the four-fold hierarchy from the world of mortals to the universe itself. Gods, animals, hymns, seasons, were all mapped into the varna system so that, as professor Brian K. Smith wrote in his book Classifying the Universe (1994): “…certain humans could present what was an arbitrary social status or status claim as natural and sacred…”

The Rigveda title sheet in the Saraswathi Mahal Library collections

| Photo Credit:

R. Shivaji Rao

Contest over the meaning of dharma

The next step in the evolution of caste happened in the context of a vigorous resistance to it from the sramanic religions. Buddhism and Jainism refused to acknowledge the authority of the Vedas, condemned animal sacrifices and accepted into their monastic orders people from all classes. Emperor Asoka’s espousal of the cause of ‘dhamma’, without mentioning varna, queered the pitch further. In response, newly composed Dharmasutra and Dharmasastra that lay down the rules of conduct for members of the Brahmanical society restated the varna ideology with vigour and patterned it into every nook and corner of Arya custom, from the cradle to the pyre. Manusmriti (or Manava Dharmasastra) was only one of many similar texts written around the beginning of the Common Era.

Dharmasutras

But when these texts were being written, the varna hierarchy was far from commonly accepted. Buddhism, especially, was experiencing the kind of expansion never before seen, riding a wave of prosperity caused by booming trade. But this would change when, between 235 CE and 284 CE, the Roman Empire was hit by a crisis that almost brought it down, the Kusana empire started disintegrating, and world trade was disrupted.

The next source of prosperity, however, was already evident: the deepening and widening of agriculture across the subcontinent. This could only happen if millions of people were drawn into the agricultural system as labourers, especially as farm settlements moved into the lands of forest-dwelling or semi-nomadic groups. And this was a humongous task, which the dozens of new kingdoms that came into being took on eagerly from around the middle of the first millennium CE.

In this task, they found the social framework based on a hereditary hierarchy useful. To implement the new system — and to lend it legitimacy — many kings, including those professing Buddhist or Jaina faith, invited brahmanas from Aryavarta to come and settle in their kingdoms on lands granted to them. Following this, the varna-jati system, whose two core principles are (a) an alliance between the ruling and priestly powers, and (b) ‘an ascending scale of reverence and a descending scale of contempt’ as Ambedkar put it, spread to the rest of the subcontinent through agro-temple-state formations in the first millennium CE.

This will shape many social attitudes, perhaps leading sociologist Dumont to think up the concept of Homo Hierarchicus in 1966, but without paying attention to the long resistance against it and the way it was shaped by political and economic contingencies. Thirty-five years later, anthropologist Nicholas Dirks would publish another last-mile snapshot of caste in his book Castes of Mind, but without paying attention to the step-by-step evolution and geographical expansion of caste.

What we know now is that caste was historically contingent in its origins and socially contested throughout its history and eventually gave rise, in the 20th century, to Ambedkar’s call to ‘annihilate’ it.

The writer, author of Early Indians, is working on a sequel focusing on India’s cultural formation.

NB: This article does not make a hard distinction between varna and jati because in the ancient texts we are dealing with, there is no indication that the two were treated as different systems.