Almost every Communist village of Kerala’s northern Malabar has a Martyr’s Column and a library. My village, Madikkai in Kasaragod, has a memorial for slain DYFI leader, comrade Bhaskara Kumbala, and a library built in memory of Communist revolutionary A.K. Gopalan. They say libraries played a significant role in shaping Kerala’s reputation as an erudite State. And like many others, it is from one of these tiny, tiled-roof libraries that my world opened up.

I first heard of Victor Hugo from an uncle one summer afternoon, while we were building castles with wet mud in a palm orchard. He said to us children: “All of you should definitely read Victor Hugo’s Pavangal [Les Miserables].” That must have stayed on, for one evening I found myself at the library waiting for comrade Kottan, the librarian, to get there. He also had a job in a beedi company. As Kottettan (brother Kottan, as I used to call him) came in, I eagerly asked about Pavangal. With a torch torch in hand, he led me through the book-lined shelves of the dimly-lit, sparsely furnished library. However, we could not find the book that day.

Visitors at the Notre Dame

| Photo Credit:

Thulasi Kakkat

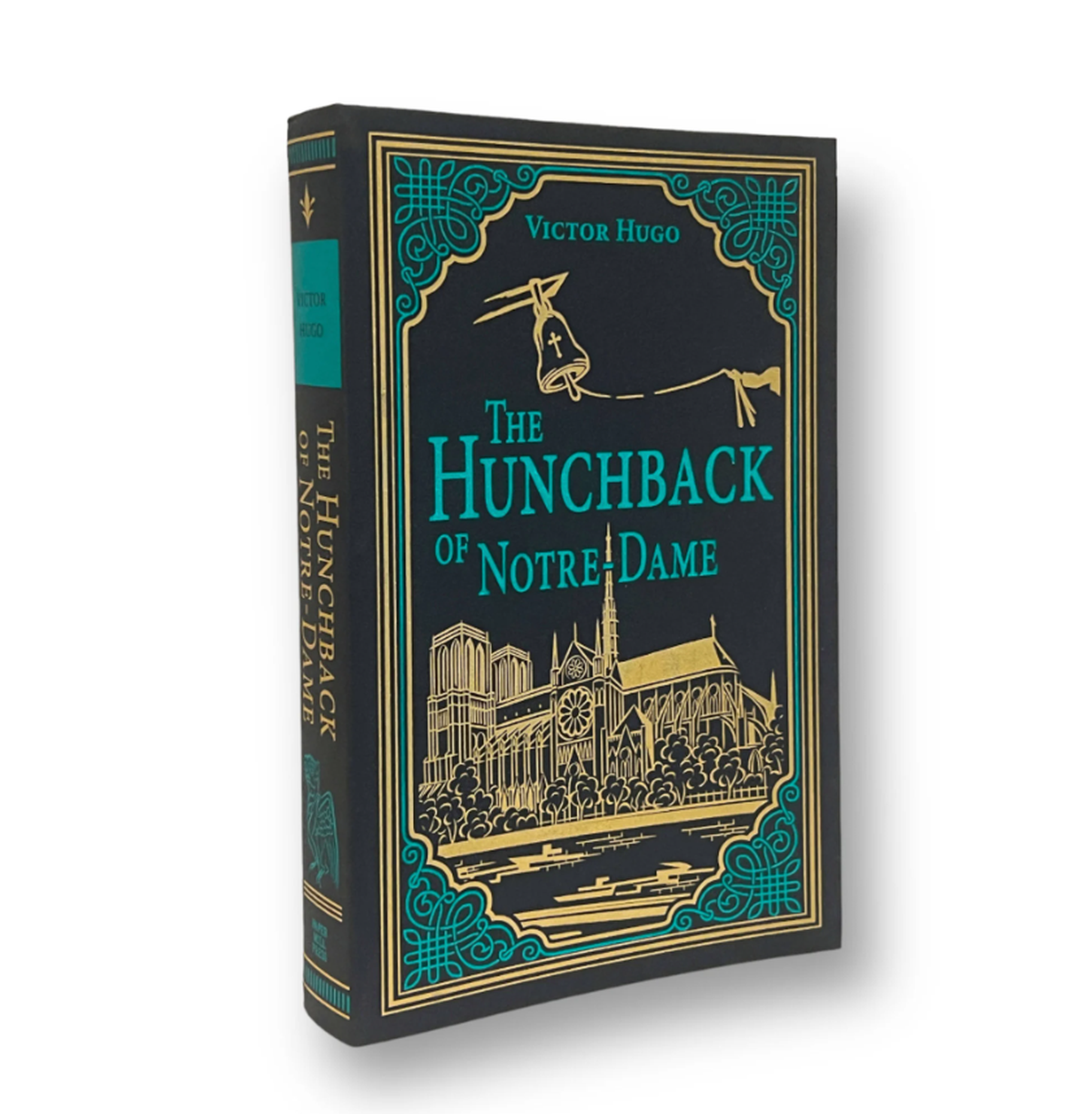

Instead, he handed me another one, Maxim Gorky’s Amma (Mother). A few days later, Kottettan told me he found the book I had been looking for. But it turned out to be another one by Hugo, Notre Damile Koonan (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame). And that was the beginning of an experience I cherish to this day. In that dingy library, I read about the famed winters of St. Petersburg, the medieval cathedrals of Paris, and the cobbled streets of ancient cities. I felt a deep sense of anemoia — a word the dictionary describes as nostalgia for a place one has never been to. In a village with only harsh summers, brooding rains and a mere whiff of spring, I yearned for the alleyways of strange cities, their biting winters, and golden wheat fields.

Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Leaning into the familiar

This January, on a particularly cold evening, while walking across a bridge over the Seine to the Notre-Dame de Paris, I felt a sense of familiarity — the memories of what I had read intertwining with real life.

It had only been weeks since the cathedral, which was shut for restoration following a fire in 2019, was reopened to the public. Overwhelmed, I felt an urge to shout out to the tourists queuing to enter the cathedral that beneath the ground upon which they were standing, once upon a time, there had been 11 steps. I had read in The Hunchback… that the steps leading up to the cathedral had been destroyed by the repeated flooding of the Seine. As I stepped inside Notre Dame through the triple-arched entryway, I was struck by how much I remembered from the book. Did I hear someone call out “refuge” from behind the altar? Did I hear a faint Spanish lullaby from some secret chamber above? Or did I spot a lamb running through the maze of the visitors’ feet?

Glimpses from inside Notre Dame

| Photo Credit:

Thulasi Kakkat

Though I knew I wouldn’t find it, I kept looking for a word. On the floors speckled with sunlight filtering in through the coloured glass windows, in the gloomy corners with giant sculptures, on the walls adorned with pictures — ANArKH. Hugo, in his preface to the novel, says he chanced upon this mysterious word, meaning fate in Greek, casually scribbled on one of Notre Dame’s towers.

“… The man who wrote that word upon the wall disappeared from the midst of the generations of man many centuries ago; the word, in its turn, has been effaced from the wall of the church; the church will, perhaps, itself soon disappear from the face of the earth,” he writes, also alluding to the state of disrepair the cathedral had fallen into in the early 19th century. The Hunchback of Notre-Dame helped renew interest in the building and led to the efforts in its restoration.

Notre Dame at night

| Photo Credit:

Thulasi Kakkat

Over 860 years old, the cathedral, a masterpiece of Gothic architecture, took 200 years and thousands of workers to build. Scores of artists and sculptors whose works it holds, the ordinary and the extraordinary people whose prayers and silences it has witnessed. Does this colossal monument know just how many lives have been linked to it in innumerable ways? Lives like mine?

Published – September 12, 2025 06:40 pm IST