In much of Southeast Asia, the idea of a bar is slowly being reshaped. Instead of music competing with chatter or cocktails, listening rooms are inviting people to slow down, sit back and actually hear what is being played.

In Bangkok, the culture is particularly visible. At Siwilai Sound Club in Bang Rak, one floor is reserved for jazz and another for vinyl. Freaking Out the Neighborhood, hidden on Sukhumvit 36, feels more like a friend’s living room than a bar, with albums played whole and a crowd that arrives to listen rather than talk over the music. And then there is Lennon’s, a high-rise bar with a collection of over 6,000 records, where you can browse, request, and settle into a late evening.

The 33-seater Middle Room in Bengaluru is an audiophile’s dream

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Hong Kong has had its own version of the movement for years. Potato Head’s hidden Music Room built a reputation with its wood-panelled interiors and collection of thousands of records, while Melody in Sai Ying Pun continues the Japanese listening-bar tradition with carefully designed acoustics and low lighting that places the music first.

The concept of the listening bar traces back to Japan in the 1940s. After Second World War, when the country was reeling from devastation and poverty, the entertainment industry too was in shambles. People would gather in small coffee shops, called kissa, to listen to music played on transistors. What began as an intimate form of communal listening has, over the decades, evolved into a global phenomenon.

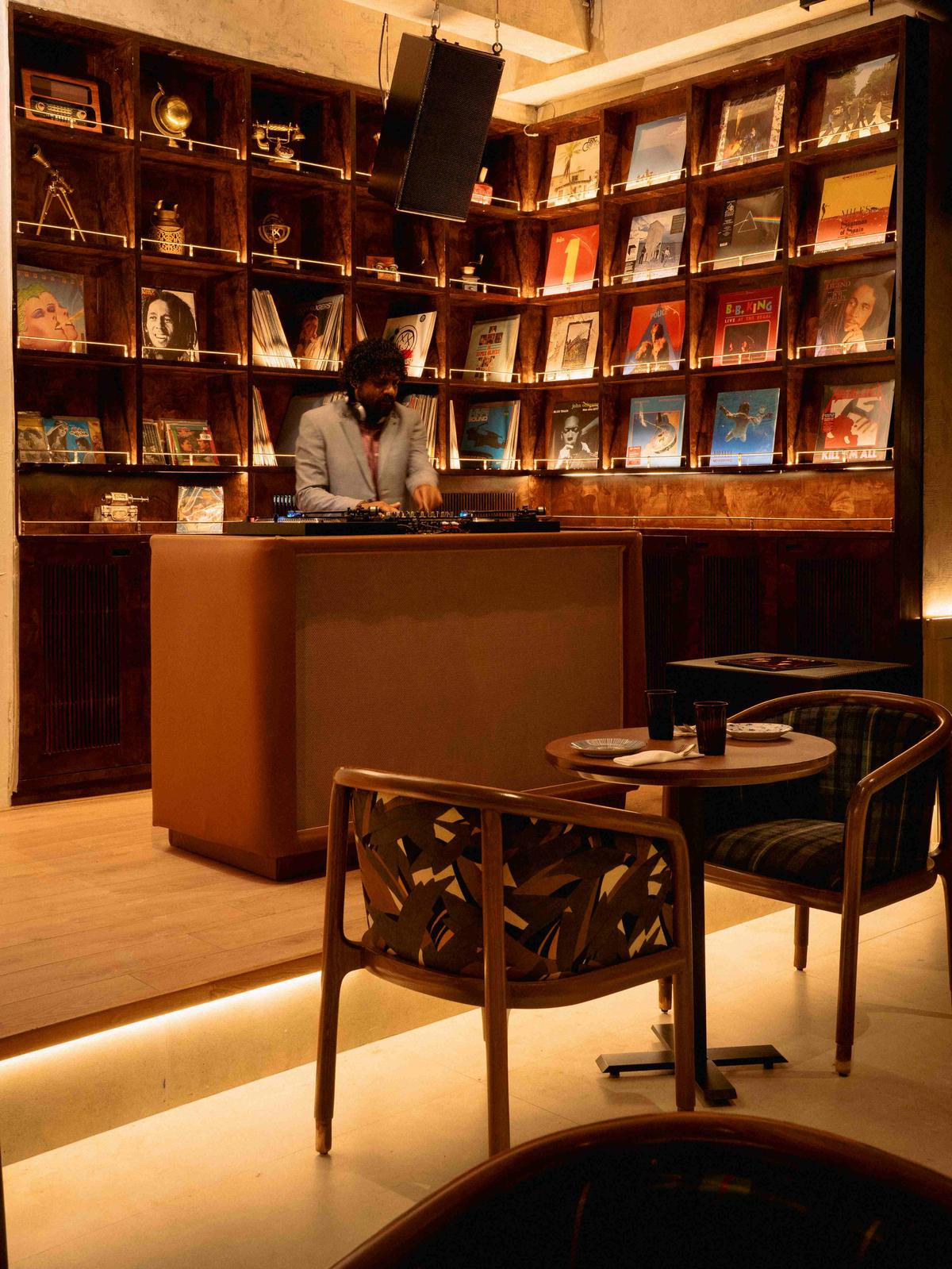

The cocktail programme at Baroke doesn’t take away from the superior sound

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

In India, the listening room remains a young idea. Collectors exist in every major city, but spaces that place music at the heart of the night are still rare.

Put that record on

At The Dimsum Room in Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda, a listening room (1,000 square foot) opened in February this year, tucked within the restaurant. It seats just about 40 people, dim-lit and acoustically treated, with a gently pitched ceiling and huge speakers.

The Listening Room at Dimsum Room

| Photo Credit:

Manan Surti

Mayank Bhatt, founder of All In Hospitality, which runs The Dimsum Room, insists this is not another restaurant with background music. “People often equate listening rooms with vinyl bars, but in many vinyl bars the music becomes an afterthought. What I wanted was a space where the music is part of the reason you came, loud enough to matter, but not so loud that you cannot lean over and chat. A space where vinyl lovers feel at home.”

For Mayank, the choice to dedicate valuable real estate to a listening room was deliberate. “If I were to make it a private dining space, I could be making ₹50–60,000 a night,” he admits. “But I’m committed to keeping this restricted to listening, to vinyl. Food and drink are served, but they’re not the point. They’re just an add-on.” To build the space, he collaborated with Kapil Thirwani, director at Munro Acoustics India and an expert in sound and acoustic design.

The Middle Room team

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Just a few miles away, another variation on the theme has appeared at Baroke, inside Krishna Palace Hotel, Nana Chowk on Mumbai’s Grant Road. The hotel itself has long been associated with Mumbai’s nightlife, and Baroke feels like a reinvention of that legacy. Here, the idea is not a hushed listening room but what founder Saurabh Shetty, director at Krishna Palace, calls a listening bar. “The listening room concept ensures people don’t mind sitting in one place with a drink, just listening. That’s a lot to ask of a Mumbai crowd. So we re-christened ourselves a listening bar in July this year, where music is still first, but the bar experience matters too.”

The attention to detail is obsessive. “We actually have a decibel metre on the DJ console,” says Hector Kavarana, marketing and communications lead at Baroke. “The loudest our music goes is 85 decibels. DJs can see it, sometimes even patrons can. It’s our way of ensuring Baroke doesn’t slip into becoming just another loud club.”

At Baroke, the collection spans about 220 vinyls across genres like rock, pop, reggae, disco, and even a little instrumental.

Inside Baroke

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

For those who want solitude, the bar has headphone stations — where guests can plug in and tune into the vinyl directly, even if there’s chatter nearby. The bar also worked with a sound consultant to install Klipsch La Scala speakers — handcrafted, imported, and rarely found in commercial spaces in South Asia.

Curation is central. The programming handled by a veteran of Mumbai’s vinyl scene, Wilber Texeira, curator of Baroke’s weekend nights, is a renowned DJ and sound designer. “It looks simple enough,” Saurabh notes, “but there’s a lot of music science that goes into even a Tuesday night. And unlike a regular club, we don’t take requests.”

A new concept

In Bengaluru, the mood shifts again at The Middle Room, which opened in July this year. The 33-seater listening room, which has a designated space from the main cocktail bar, operates on time-slot bookings, offering listeners two-hour windows to settle in with music. Inside, wood and red accents set the tone, warmed further by a sleek Technics SL-1200 MK7 turntable from Tokyo and a wall stacked with over 1,000 LPs.

Baroke

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

For Akhila, the balance is delicate. “We can capitalise on the bar, but it’s very hard to just monetise. What we realised early was that we needed to be clear about what we really wanted to focus on. While we’ve put a lot of attention into the food and drinks, we were very clear from day one that the sonic experience would be at the heart of it.”

To achieve that, they engaged two senior programmers to shape the listening experience, right down to sequencing tracks for each slot. “Bengaluru once had a big, vibrant live music scene that isn’t as visible today. This project leans into that memory, and people have responded warmly. At the same time, we also see guests who come because it’s a new space and they’re curious,” says Akhila.

A night out at Middle Room

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

For Hyderabad-based duo DJ and producer Sri Rama Murthy, who goes by Murthovic, and creative director Avinash Kumar aka Thiruda, who helm a transmedia art project called Elsewhere In India, curating the sound at Middle Room is as much about investing in community as in sound. “We didn’t want just a hi-fi home setup but something immersive, a hybrid between a listening space and a small performance venue,” says Murthovic.

To do that, they brought in a Danley Labs system, designed by former NASA scientist Tom Danley, known for his patented speaker technologies. “We also went to Japan to buy Technics turntables — still the gold standard — and added an all-analogue rotary mixer for warmth and clarity. The room itself was treated like a studio — from the acoustics to the lighting.”

Murthovic and Avinash also see the space as a hub for dialogue and exchange. Alongside gigs, they host talks and workshops in collaboration with local sound researchers and engineers.

New and old listeners

In Goa, the concept is taking a more relaxed shape. For The Record, tucked into the heritage lanes of Panjim, is not strictly a listening room but a vinyl-led café-bar. It is drawing in a younger crowd who are still easing into the culture.

Goa-based photographer Daniel D’souza, who is in his mid-20s and a regular, sees it as something different from the State’s usual nightlife. “The food and cocktail programme is top notch,” he says. “They were playing a Daft Punk vinyl one night, which was great. The music is thought of, and the whole concept is just different from a regular bar.”

For vinyl collectors, the appeal of listening spaces lies less in nostalgia and more in fidelity. Mumbai-based content creator and entrepreneur Aneesh Bhasin, who has built a sizeable vinly collection over the years, believes what matters most is the set-up. “If you’re going to get a cheap turntable and hook it up to a regular Bose speaker system, there’s no point apart from it looking cool. You’re actually better off streaming music,” he says. For Aneesh, who owns a vintage 1978 Luxman amplifier from Japan and a German ELAC speaker system, vinyl is about extracting every layer of sound. “It’s not a cheap hobby. If I’m buying a record at ₹3,000 on average, I want to get the most out of it.”

Still, he admits to a concern about India’s emerging listening culture: “My only reservation is that the owners and promoters are putting in the work, but how many people are actually caring about the sound? I hope that changes, and it doesn’t just become background noise when you’re dining.”

But for all the romance around vinyl and sonic immersion, there is also the hard arithmetic of running such spaces in India. Diganta Chakraborty, Bengaluru-based founder and CEO at Elemental, which operates across three spheres of F&B — own spaces, client solutions, and curated experiences — puts it plainly: “You can’t have it small in Bengaluru. The alcohol licence itself costs a crore. If your total expenditure is ₹2.5–3 crore, you need to make that money back in four or five years, which means the space has to be larger.”

From his perspective, listening rooms are only viable when it is folded into a bigger revenue-generating bar. “You have a cocktail bar that’s making the money, and within it you create a listening room for 30–40 people. The moment it becomes too large, it ceases to be intimate, you’re just listening to what others want you to hear.”